(Not) Seeing Colors

(Not) Seeing Colors

I'm color blind. No, not in the way you might be thinking, that of pointing to a bright red car and asking, "What color is that?" Uh, no. I can see colors fine, just not the fine shadings between some of the pastels such as when someone says that there's a little pink in that gray swatch...really? And if you're already saying that you're not color blind, you can (privately) take any of the simple colorblind tests, although the more extensive ones will get into more and more detail, narrowing down the shades that you are unable or less able to see, be they browns or grays or greens. |

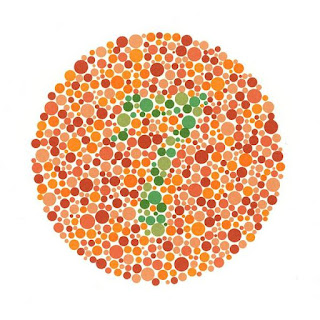

| What image, if any, do you see? |

Colorblindness primarily affects males (on average, about 5-10%), although females sometimes can be colorblind; and colorblindness is fairly spread out over the world, ending the myth that certain nationalities are more prone to being colorblind (a myth perhaps started more on a cultural basis than on a scientific one). And to end another myth, many animals (including fish) can and do see color, often many more colors than we do (without going into too much detail of how the eye works --rods and cones in the retina-- the cones are what enable us to distinguish color).

And lest you feel a little smug about not being colorblind, there are all levels of seeing color and some (a very few) see millions more colors than the average person (since the grading of additional cones are exponential, the normal person sees about a million colors...the additional cones in these rare individuals allows them to see about a hundred times more than that). Scientists seek these few individuals, newly termed as tetrachromats, to study why they have an extra set of cones in their eyes and what, exactly, are they seeing, all detailed in an earlier article in Discover magazine. And to place us humans down another notch, our visible world is quite limited overall (birds and insects can see more of a light range than we can, in just one example a small mantis shrimp has 10 more color photoreceptors than we do)...as mentioned earlier in NOVA Earth From Space, if the light range were stretched from New York to Los Angeles, the range of light we humans can see would be the size of a dime...about half an inch!

Much of the credit for discovering the source of color goes to Sir Isaac Newton in the 1600s, famous for his portraiture of his holding a prism casting a rainbow of lights nears a window. But the Romans had already been experimenting with color over a thousand years earlier, as discovered in a glass goblet that changes colors when lit from the back. In a brief article in Smithsonian, they write:

The glass chalice, known as the Lycurgus

Cup because it bears a scene involving King Lycurgus of Thrace, appears

jade green when lit from the front but blood-red when lit from behind—a

property that puzzled scientists for decades after the museum acquired

the cup in the 1950s. The mystery wasn’t solved until 1990, when

researchers in England scrutinized broken fragments under a microscope

and discovered that the Roman artisans were nanotechnology pioneers:

They’d impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold, ground

down until they were as small as 50 nanometers in diameter, less than

one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt. The exact mixture of

the precious metals suggests the Romans knew what they were doing—“an

amazing feat,” says one of the researchers, archaeologist Ian Freestone

of University College London.

Such a use of color is being used by a pair of artists (Carnovsky) in Milan, different scenes appearing on the same palette when shown under different colored lights. Much the same is being discovered among poisonous frogs in Central and South America, their bright colors seemingly displaying the intensity of their poison (and attraction for the opposite sex). What was a surprising addition to this discovery was that the colors seem to be predator-specific as well, the birds that prey on them less able to distinguish brightness in colors, and the snakes that prey on them more able to distinguish infrared colors (we humans cannot see the infrared spectrum).

Such a use of color is being used by a pair of artists (Carnovsky) in Milan, different scenes appearing on the same palette when shown under different colored lights. Much the same is being discovered among poisonous frogs in Central and South America, their bright colors seemingly displaying the intensity of their poison (and attraction for the opposite sex). What was a surprising addition to this discovery was that the colors seem to be predator-specific as well, the birds that prey on them less able to distinguish brightness in colors, and the snakes that prey on them more able to distinguish infrared colors (we humans cannot see the infrared spectrum).

Back in my day, the colorblind were actually sought by the military, their ability to penetrate camouflage appearing as easy to them as it was puzzling to those with normal color vision. Of course, the colorblind could not become pilots (still true today for the military, although becoming a pilot for a civilian aircraft is possible even if you're colorblind). Also back then, simple tasks such as repairing phone lines meant color testing with a cable strand, one filled with close to fifty different-colored wires (I failed, but I can still see the importance of the test, connecting the right colored wire whenever I pass an open relay box, its hundreds of wires hooked together in an elaborate maze...and no, I'm not good with electrical wiring either). Today, technicians have instruments that detect colored light so that even the colorblind can now work and connect the lines.

But utilizing color is something more and more scientists (and now marketing people) are studying. Out go the calming "pink" rooms (not true) and red fire trucks (yellow is more visible to our eyes). Red clothing is proving confrontational (but increases tipping among men to female waitresses) while blue articles such as ties can prove a willingness to negotiate (black uniforms still tend to invoke aggression which makes one wonder why so many police uniforms are still black). Ironically, one of the first commercial people to believe in the effect of color on people was Walt Disney when he was designing Disneyland. Meeting with a group of psychologists, he paired colors to match his lands, the creams and yellows of Main Street, the silvers of Tomorrowland, the browns of Frontierland. It was a radical experiment at the time, but one that would prove ahead of its time (Professor William Lidwell talks extensively of how colors affect you during his lecture series from The Great Courses).

Even more extensive are people with a neurological condition called synesthesia, whose senses "blend" in a sense so that a smell or a touch displays a color in their minds. An earlier article in Bloomberg Businessweek described a bit of this condition: “When I learned to read and write as a child, I discovered that six is orange and seven is yellow, and I thought everyone knew that,” Haverkamp explained during the 10th Annual American Synesthesia Association conference, hosted by Toronto’s OCAD University last spring. Experts say the condition, usually inherited, likely affects 1 in 23 people. That includes a large number of leaders in their respective fields: Lush cosmetics co-founder Mark Constantine; Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman; Robert Cailliau, one of the creators of the World Wide Web; Billy Joel; and many more. Pharrell Williams, a musician and producer behind this summer’s hit songs Blurred Lines and Get Lucky, would be lost without his music-to-color synesthesia. “If it was taken from me suddenly, I’m not sure that I could make music,” he said in an interview. “It’s my only reference for understanding.” Now car companies and others are trying to incorporate some of these observations into their marketing, perhaps subconsciously affecting our decisions or (dis)comfort.

Those of us who are colorblind might be able to change that in the near future as scientists are already splicing genes into mice and noticing some results. But imagine going a step further and scientists turning us all into tetrachromats and "synners" and opening up a vast array of new colors and sensations. Our world would change again, for had there been a slight shift in our atmosphere when it developed, we would have evolved with an entirely new spectrum of light, one that shifted more toward the ultraviolet spectrum and not that of the current spectrum of colors that we now see.

In a sense, we are all colorblind to different degrees. But only now are we finding how yet another field that we take for granted is proving so essential to how we feel. From food to someone's eyes, we are both drawn and repulsed...but perhaps all of it is merely how we decide to see, for there seems to be an entirely new world just beyond our line of sight.

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.