|

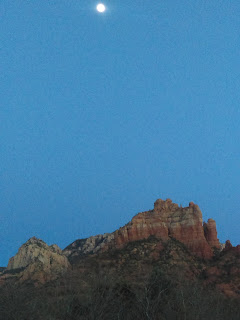

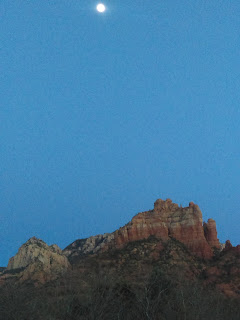

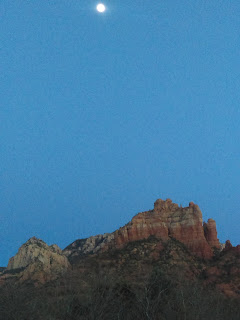

| The Moon over Sedona |

Certain places seem to almost pull you outside with a gentle force, something that we've found here in Sedona and as with many places, something we became even more aware of as we departed; as with many a vacation spot the towering cliffs and deep crimson colors of the ancient layers in this area seemed to lure us out at a steady pace, much as the lapping waves on a beach seem to do after an hour or so spent tanning in the sun. For my wife and I, it's always exciting to see so many people out on the more popular trails in Sedona, from families with young adults to elderly seniors who seem ill-prepared for the heat and the length of the trails ahead...but they're out there trying so bully for them. Add in the seasoned hikers and bikers, some just visiting and others being locals who have yet to tire of the spectacular vistas (one of the young mothers waitressing us at lunch went hiking almost daily), and you can sense the energy that this place seemed to emanate. So what is it about getting out to nature in general? What makes some areas so attractive and others less so? For some, the appeal of getting out might lean more toward a luxury hotel or restaurant while for others it can be a trip working with villagers who have little. For us, as we were now again departing and facing the long ten-hour drive back to our home, I wondered about some of this and why --even with our touristy eyes-- we were still enamored of this area. Was it, as

Scientific American Mind put it, that we were recognizing that: ...

seeing nature makes us think more about the future.

|

| An exhausted biker near Bells Rock, Sedona |

Another interesting piece appeared in the same

magazine, this one asking why we imagined.

We use our imagination in many ways. Novelists rely on it to dream up plots, characters and scenes. Artists use it to conjure new works. Children entertain themselves by weaving fantastical worlds in their minds. For adults, however, one of the most common --and underappreciated-- uses of imagination is counterfactual thinking. We dip into alternate realities with a frequency and ease that suggest this habit is core to the human experience...When we muse about the different ways an event might have unfolded, we tend to be predictable: we alter certain parameters but not others. The gist of the article was that we lean toward changing the what-could-have-been, the blaming ourselves when something goes wrong, the if-only thoughts. If only I had gone a different direction, if only I had visited more, if only I had checked the car fluids before I left. Often, these thoughts usually occur after an event such as an accident or something regrettable, although it can veer the other way as well say when hitting a jackpot and thinking wow, if I had left a minute earlier that never would have happened. But here's what the article added:

Imagination, it seems, helps us to transcend the reality of the immediate present to come to grips with our past and prepare for the future. Exploring the unreal may be an important step in finding meaning in, and shaping the narrative of, our everyday lives.

|

| Devil's Bridge, a popular arch people cross |

For me I wondered if that was our draw here, to "find meaning in, and shaping the narratives of, our everyday lives." But I also had to wonder...if the skies turned hazy and we could no longer see much of the distant cliffs (as has happened during certain days in the Grand Canyon, obscuring its grand vistas) would I find this area as attractive? Was I just ready for a change and if so, of what? Of climate, or location, of attitude; of was it simply the fact that this area provided a temporary escape and that that in itself was the draw? Or was it my imagination, that "counterfactual thinking" that was only picturing the greener grass next door? Back in the room, I read a piece in

Discover about our national parks, how they are now facing large budget cutbacks from the new administration in Washington and how this once "best idea" of creating national parks (as the article mentioned:

Half the world's geyers have been destroyed, but geologists can still study them in the protected environment of Yellowstone National Park) might become areas where, as one biologist told the author:

We might not be able to keep glaciers in Glacier National Park. Instead, we may have to manage for change based on projected future conditions. Our parks have become a telling series of ongoing discoveries for scientists, from studying the effects of restoring a river's flow by removing a dam (Olympic) to watching a devastated forest recover (Yosemite), and from observing the curling river patterns in a marsh (Everglades) to the effects of native animals and plants as the climate warms (Haleakala). In Arches, some researchers are placing sensitive seismometers on a few of the arches to check their vibrational "signatures," something even I worried about as I watched people standing atop Devil's Bridge in Sedona (in 2008, one of the largest arches in Arches National Park collapsed in the night).

|

| Sunrise as we drove away |

Perhaps it was all simply too much thought, adding detail when a painting was already finished. We packed our bags and loaded the car, the morning sunrise greeting us gently as if giving us a final tease. The weather would soon heat up, even in these early months of spring. And really, wasn't the point of getting away to do just that...get away. The moon had cast a beacon on the night before we left, a light that appeared to be renewing our

charging or perhaps re-charging since our thoughts and worries had been

cleared. We had been treated to a cleansing of sorts, a restoration;

and despite returning to tax deadlines and politics and looming bills, we were now starting afresh.

The Economist wrote about our viewing of time and how:

It ticks away, neutrally, yet it also flies and collapses, and is more often lost that found. Viewed differently, the article dispelled one of our common perceptions that we have less time:

On

average, people in rich countries have more leisure time than they used

to. This is particularly true in Europe, but even in America leisure

time has been inching up since 1965, when formal national time-use

surveys began. American men toil for pay nearly 12 hours less per week,

on average, than they did 40 years ago—a fall that includes all

work-related activities, such as commuting and water-cooler breaks.

Women’s paid work has risen a lot over this period, but their time in

unpaid work, like cooking and cleaning, has fallen even more

dramatically, thanks in part to dishwashers, washing machines,

microwaves and other modern conveniences, and also to the fact that men

shift themselves a little more around the house than they used to. And so here we were, spending that gained "time" and staring at grand old rocks that seemed to be withstanding their own "test" of time; magnificent geologic wonders on a grand scale, pillars of dirt and stone that had continued to spark our imaginations. And almost as suddenly, as we drove off, it dawned on me. This was indeed about time, but not about what was or what would be, but rather of just recognizing what is. This could be anywhere for anyone, a hillside in Italy or a vast expanse of coastline, a piece of desert or a tangled forest. The location didn't matter; as one woman at a local shop mentioned, a place either lures you or it doesn't. I was thinking way too much...driving away I was already falling back into my mode of thinking of what was awaiting me at home. But before that, I realized that Sedona had made me forget it all just by letting myself walk among and be caressed by the rocks. It was a time I was meant to set as a "restore" point, a secure place where I could return to just in case I crashed and needed a reboot. Nice job...now the ten hours could approach with ease. I was ready.

|

| Our goodbye to Sedona...for now |

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.