Leperd

The spelling is incorrect no matter how you look at it. The animal would be spelled leopard, its spots (and whiskers) as distinctive as our freckles or fingerprints, which is often how animals biologists keep track of them.* And then there are lepers, as in those in a leper colony; and even there the spelling for the affliction becomes leprosy. The skin disease is both treatable and curable (often within 6 months if caught early enough) and spreads with a sneeze or cough. But the thing is, I somehow thought that --as with smallpox-- it was basically no longer. Such was the reaction early in Dr. Victoria Sweet's career when she was puzzled about a patient and was told by the attending doctor: "Well see, it's the ulnar nerve hypertrophy here," she said, showing me the lumps at Jose's elbows, "And the distal wasting here." She showed me his fingers. "The nerves at the elbow enlarge, and that damages the nerves to his fingers, so they get numb and then he burns them or knocks them without realizing it, and the fingers auto-amputate." ...Jose didn't seem surprised by his diagnosis. He thanked me, took his referral and left, and that night I took down my books and read about leprosy. The two kinds of leprosy, the lepromatous and the tuberculous, the relationship to armadillos, the lack of acute contagiousness of such a dreaded disease. Turns out, however, that Dr. Sweet was more imprinted with how the doctor did the examination: As I watched her scan Jose and then examine his elbows, she wasn't so much thinking as feeling, performing a quiet, unhurried search inside a huge experience, not linearly but globally, feeling around in her Self for that wholeness, that solution which is the right diagnosis and fits all the clues. She goes on to define the backgrounds of a few terms: "Nature" from the Latin natus, from nasci --to be born-- so "Nature is what you are born with, who you are. In Greek, "Nature" is rendered as physis, which is the root of physician, and which comes from the verb phuein -- how a plant grows. None of us is a stranger to physis -- we all know that plants grow, produce flowers and fruits, die, and then grow back again. We even know human physis. We see it all the time -- the cut that heals, the cold that goes away, the bruise that resolves, the fracture that even modern medicine can only set to heal on its own. But we never think about it...

She also mentions something that I wasn't aware of, this from her recent book, Slow Medicine...the definition of schizophrenia; Wikipedia rather extensively gives its background but basically says schizophrenia is something: ...often described in terms of positive and negative (or deficit) symptoms. Positive symptoms are those that most individuals do not normally experience...Negative symptoms are deficits of normal emotional responses or of other thought processes. Dr. Sweet writes about one definition of schizophrenia being coined as not a "split" mind but rather, a "loose" mind. Indeed, as I would see during that year, the schizophrenic was all over the place, his speech tangential and circumstantial, and his metaphors not symbolic but real. During her internship in psychiatry, she learned to simply observe...how did a patient entered the consultation room? Stiffly? Restlessly? Like a wild animal on soft feet, smelling around the corner, ears up? Cocking his head to better hear his voices? Was his speech rapid and all over the place -- pressured, tangential, and circumstantial? Was he excited? Or slow-moving? Ponderous, heavy? Later as a doctor, she would often pull this into her practice, observing and asking first --how the patient was feeling, the background, the family history, what was going on in that person's life-- and then, later, look at the patient's chart. Often, her treatment proved both easier and more accurate.

There's a word there, patient. Be patient as well as be a patient. How often in life do we zoom through it, trying to capture it all and probably actually missing most of it. The tourist in Rome, rushing to see the Colosseum, the Forum, the fountains, the steps, the plazas and yet not stopping at a quaint café to just leisurely soak it in, to chat a bit with a local or two or twelve. My wife and I have done both, that quick see-it-all and also the hours we spent in a pub in Germany (we stayed and visited and had such a good time that the husband-wife owners offered to buy our drinks if we would stay...we would have except that our host, looking for us, finally found us and wanted us back). Doctors too might face the same quandary, exemplified by my own just completed physical; despite our years together (same doc for nearly 30 years), he had so many patients that my exam was thorough but not chatty. When I noticed that he needed to check out one spot on my arm I was worried about and yet forgot to ask him about, I was planted back into a waiting room and there, 20 minutes later, we ended up talking not of the spot on my arm (no biggee, it turned out) but of our favorite brands of scotch.

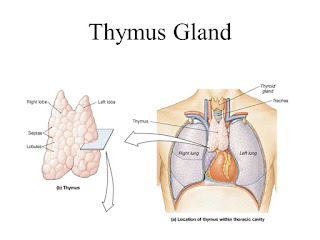

Sometimes that sitting out on a deck or in the park or at a café and looking at nothing -- no phone, no laptop-- is healing. To observe without judgement. To be patient. To be open. And to question. One example of locking in a conclusion revolves around the thymus gland. Doctors in the late

1800s were still studying the human body by dissecting them, but bodies were quite difficult to get. If you were poor, your body was often dug up as soon as you were buried (generally being in a shallow grave), which led to the term "grave robbers." The wealthier could afford to both bury bodies deeper and to provide guards at the gravesite and at the hospital (this was the period when the "sealed" casket was invented and patented in order to make it more difficult for thieves to access and steal the newly buried body). One bad result of this was that the majority of the bodies studied, especially those of babies and children, were often not indicative of a healthy body; poor nutrition, disease, and compromised bodily systems, led to glands and organs that were less than optimal for studying. In the case of children, the thymus gland was quite small in the poor (one of the factors that shrinks the gland is stress). But this time period also marked the noticeable start of SIDS or Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (ironically, this was something suffered mainly by the wealthy who had the time to put their babies in cribs and beds and basically out of sight, a luxury often not available to those wracked with poverty). A doctor noticed upon examining such children that had died from SIDS that their thymus glands were overly large; this was observed over and over and soon led to the medical practice of irradiating babies early in order to prevent the thymus gland from growing to such as size, a practice that lasted well into the 1920s (and even up until the 1950s in many areas). Of course, the thymus glands that were being viewed were simply the normal size -- doctors prior to all of this had been primarily viewing the smaller, shrunken thymus glands of the poor and assumed that all children's thymus glands were of this size and that this was the standard. It took other doctors decades to question the practice, noticing that babies and children that had died of causes other than SIDS (drowning, car accidents, falling off stairs, etc.) had the same "enlarged" glands. Sadly, one of the end results of this irradiating was a drastic increase in thyroid cancers (the thyroid gland sits near the thymus gland...much of this information again came from the lecture series by Professor Paul Robbins on Cultural and Human Geography).

|

| Graphic courtesy of SlidePlayer |

There was an article in The New Yorker that talked of the advances in virtual reality, software equipped viewers that can now mimic out-of-body experiences or what some would describe as astral projection. The article asked "Are we already living in virtual reality?" This caused one reader to reply that virtual reality was once only something of an escapist adventure: But (author) Rothman's V.R. experience, in which he acts both as Freud and a patient, offers an alternative. It also reveals the fragility of our self-perception and the limitations of attempts to "see another perspective." My wife and I took part of our honeymoon hiking to the leper colony on the island of Molokai (of Father Damien fame). It's normally a mule trip much like that of the Grand Canyon, the hike down and back doable but one that also came with the guides' casual warning to "make way" when we heard the mules coming. Our hike down led us to wild papayas the size of footballs (we dined on one that had fallen and was only semi-split on the ground...delicious) and the bus tour at the bottom (one is not allowed to just wander around the colony). It was beautiful. The scenery, the people, the remoteness. Our hike back was drenched in rain but we were hot and exhausted, as well as exhilarated. We had gone down with no expectations and had emerged with a new appreciation and a new knowledge. And now, nearly 30 years later, I had to re-learn that knowledge, part of which was discovering that leprosy still existed. We learn slowly at times but as long as we can stay open-minded, we can learn and re-learn. We can gain new perspectives and shed old ones. And perhaps if we take the time to slow down, to observe, we might even gain a new perspective of ourselves...positive and negative. Schizophrenic.

*An art print worth checking out is that of a jaguar by Charles Frace; rather inexpensive, he uses a technique that has not only the eyes but the entire head follow you as you view it from side to side. When and if you view it, try looking at it from the far left, then slowly move over until you are looking at it from the far right. Eeerie and yet strikingly beautiful in its element...and if you haven't yet watched the sandhill crane migration, here's your chance as National Geographic runs a short 5-minute episode on the birds annual stopover in (of all places)...Nebraska.  |

| First Light by Charles Frace |

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.