The Birthing of Creativity

Life -- we are surrounded by it, watching it grow, living it, seeing it everywhere. But as the late anthropologist, Loren Eiseley, said, "Seeing is not the same thing as understanding." We --with some 100 organs, 200 bones, and 600 muscles-- are filled with life, yet we still wonder why an unborn child who is moving, kicking, and so comfortably alive in his mother's womb can tell us more about life than anything we could describe. We are filled with expressions (we have more separate muscles in our face than any other animal), yet still wonder why a baby's hazy stare and girgling laugh can so unspeakably describe our own happiness. We are among the one percent of animals that are warm blooded and are equipped with inner machinery so delicate that only a few atoms out of the billions in our blood are enough to prevent disease. Yet we have little idea of what keeps it all working, this perfect blend of thoughts and dreams, of love and emotion.

So where does it all begin, this mating of the body's largest cell (the ovum) with one of the body's smallest (the sperm)? What spark triggers this tiny union --no bigger than a pin point-- into a beating heart four weeks later, cells that have increased in size 10,000 times in the same period, well under way to their finished body of 60 trillion cells (each of which contains the genetic information for creating yet another life). If asked to describe life how would we answer? Would we attempt to fill volumes with words or simply point to a budding flower? Would we wipe dry the mother's tear or just listen to the laugh of a child? Would we bravely describe life as one Blackfoot Indian chief did, "...the flash of a firefly in the night, the breath of a buffalo in the winter time, the shadow that runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset." Would we describe that which we feel or have felt or expect to feel? Would we try to capture that which is timeless -- the after-rain colors on a hillside, the freedom of a soaring bird, our first kiss, the birth of a child. Perhaps life itself is the definition...the wonder of it all. How is it that so dear a living being is now placed in our trust? Before the birth, we half-desperately peered inside and some nine months later saw the life that we so anticipated. And it was at that point --with or without understanding, scientifically or religiously-- that we knew life only as a gift...and still, we stare in wonder at the miracle of it all.

That was me, writing back in the early 80s (that particular piece was published by a health group that distributed its magazine in hospitals). I was freelancing, writing for inflight magazines, hospital groups, local papers, really any market that would take my eagerness, curiosity, and ramblings and (gasp) actually pay me for it. And then, something fizzled out. It wasn't the drive, per se, just that other things seemed to appear such as work and home life and realizing that making a living at writing (acting/singing/fill-in-the-blank passion) would be a life of penury...in other words, discovering the realities of life. Finding that earlier piece of my writing during my clearing out of files and such made me think back to artists and musicians and how much of their top recordings or paintings often do come in their 20s as if in a burst of creativity, that one classic album or book or movie or discovery coming early followed by a searching for a second chance at the ring which somehow proves so elusive. Life at that age, in its wild feeling of never coming to an end and with still so much to go, seems to spark far more questions and expressions of life than those of the later years of looking back (although not always; some of the opera composers, such as Verdi and Beethoven were successfully composing even near the end of their lives, in the case of Verdi well into his 80s). Why is that? As with athletes, are our bodies (and brains) just following the path of aging and diminishing in abilities? Certainly there are exceptions as some writers/actors/crafters/scientists continue their aliveness and imagination well into their third part of life (think Einstein), as if aging-in-a-barrel matures minds as well as scotches?

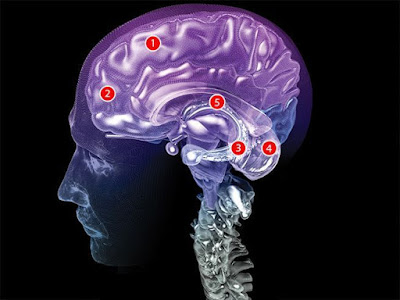

Of course time is a human creation, and the process of creating it falls back onto our brains; as one lecture series described, if we had no memories or at least no ability to store or create memories, there would be no time. This was better described in a graphic in Popular Science which, after showing the complicated channels our brains process for even the simplest memory, concluded: Neuroscientists do not fully understand the precise neural dance -- yet. The graphic summarized it this way...1) Stopwatch (supplementary motor area), 2) Memory Center (inferior frontal cortex), 3) Sequence Sorter (hippocampus), 4) Beat Keeper (cerebellum) and 5) Reward Counter (basal ganglia). Phew, who would have thunk? But then that is what makes the travel through life so exciting isn't it, the fact that we are discovering so much about both the world and ourselves. We seek to reduce lipids in our bodies by taking pills, and yet a recent firm (Apeel) has developed a way to extract lipids from several plants and make them into a powder; once re-mixed with water, the coating forms a natural edible barrier that blocks mold and other forms of spoilage by days or "even weeks." Hmm, so what exactly are the function of lipids, the ones we are preventing from doing their job in our own bodies?

Another piece in Scientific American talked of the rise of pancreatic cancer, soon to become the second largest cause of cancer deaths with big increases reported in the U.S., France, Japan and other countries. But rather than single out a reason, the article pointed out the many ways this could be happening. Said the piece by award-winning scientist Claudia Wallis: The rising rank in mortality is, in some ways, a good thing; it reflects advances in battling other malignancies. Better screening and treatment have meant that patients with other types of cancer --particularly breast, prostate and colon cancer-- are living long enough to die of something else...refined ways of testing biopsided tissue and higher-resolution imaging have meant that mystery tumors that once couldn't be seen or were labeled "of unknown origin" can now be identified...the aging of our population also contributes: it's pushing up the rates of many kinds of cancer...Other forces are at work as well. Smokers face more than twice a nonsmoker's risk of pancreatic cancer...soaring rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes, which are also risk factors...among the suspected reasons: chronic low-level inflammation, too much insulin, excess hormones and growth factors released by fat tissue, and metabolic abnormalities. And while she notes that liquid biopsies are slowly (very slowly) growing more precise, there is much we just do not understand about why pancreatic tumors metastasize so much more rapidly than other tumors; said the chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society, "The cells break away like a crumbling popcorn ball.

Perhaps this is just our journey, this discovering and solving certain mysteries while finding others. We can scan our brains and find that among the 100 billion or so neurons in our brains resides glia that far outnumber our neurons, and yet are essential for their development and survival...the dark matter of our brain. And now we solve some diseases or cancers only to discover others. Our world, our lives are a mystery and it seems that the more we peer both inward and outward, the more we discover. It's an exciting time of life, a time where age has no bearing. It's almost, once could say, time-less.

So where does it all begin, this mating of the body's largest cell (the ovum) with one of the body's smallest (the sperm)? What spark triggers this tiny union --no bigger than a pin point-- into a beating heart four weeks later, cells that have increased in size 10,000 times in the same period, well under way to their finished body of 60 trillion cells (each of which contains the genetic information for creating yet another life). If asked to describe life how would we answer? Would we attempt to fill volumes with words or simply point to a budding flower? Would we wipe dry the mother's tear or just listen to the laugh of a child? Would we bravely describe life as one Blackfoot Indian chief did, "...the flash of a firefly in the night, the breath of a buffalo in the winter time, the shadow that runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset." Would we describe that which we feel or have felt or expect to feel? Would we try to capture that which is timeless -- the after-rain colors on a hillside, the freedom of a soaring bird, our first kiss, the birth of a child. Perhaps life itself is the definition...the wonder of it all. How is it that so dear a living being is now placed in our trust? Before the birth, we half-desperately peered inside and some nine months later saw the life that we so anticipated. And it was at that point --with or without understanding, scientifically or religiously-- that we knew life only as a gift...and still, we stare in wonder at the miracle of it all.

That was me, writing back in the early 80s (that particular piece was published by a health group that distributed its magazine in hospitals). I was freelancing, writing for inflight magazines, hospital groups, local papers, really any market that would take my eagerness, curiosity, and ramblings and (gasp) actually pay me for it. And then, something fizzled out. It wasn't the drive, per se, just that other things seemed to appear such as work and home life and realizing that making a living at writing (acting/singing/fill-in-the-blank passion) would be a life of penury...in other words, discovering the realities of life. Finding that earlier piece of my writing during my clearing out of files and such made me think back to artists and musicians and how much of their top recordings or paintings often do come in their 20s as if in a burst of creativity, that one classic album or book or movie or discovery coming early followed by a searching for a second chance at the ring which somehow proves so elusive. Life at that age, in its wild feeling of never coming to an end and with still so much to go, seems to spark far more questions and expressions of life than those of the later years of looking back (although not always; some of the opera composers, such as Verdi and Beethoven were successfully composing even near the end of their lives, in the case of Verdi well into his 80s). Why is that? As with athletes, are our bodies (and brains) just following the path of aging and diminishing in abilities? Certainly there are exceptions as some writers/actors/crafters/scientists continue their aliveness and imagination well into their third part of life (think Einstein), as if aging-in-a-barrel matures minds as well as scotches?

|

| Graphic from Sinelab via Popular Science |

Another piece in Scientific American talked of the rise of pancreatic cancer, soon to become the second largest cause of cancer deaths with big increases reported in the U.S., France, Japan and other countries. But rather than single out a reason, the article pointed out the many ways this could be happening. Said the piece by award-winning scientist Claudia Wallis: The rising rank in mortality is, in some ways, a good thing; it reflects advances in battling other malignancies. Better screening and treatment have meant that patients with other types of cancer --particularly breast, prostate and colon cancer-- are living long enough to die of something else...refined ways of testing biopsided tissue and higher-resolution imaging have meant that mystery tumors that once couldn't be seen or were labeled "of unknown origin" can now be identified...the aging of our population also contributes: it's pushing up the rates of many kinds of cancer...Other forces are at work as well. Smokers face more than twice a nonsmoker's risk of pancreatic cancer...soaring rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes, which are also risk factors...among the suspected reasons: chronic low-level inflammation, too much insulin, excess hormones and growth factors released by fat tissue, and metabolic abnormalities. And while she notes that liquid biopsies are slowly (very slowly) growing more precise, there is much we just do not understand about why pancreatic tumors metastasize so much more rapidly than other tumors; said the chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society, "The cells break away like a crumbling popcorn ball.

Perhaps this is just our journey, this discovering and solving certain mysteries while finding others. We can scan our brains and find that among the 100 billion or so neurons in our brains resides glia that far outnumber our neurons, and yet are essential for their development and survival...the dark matter of our brain. And now we solve some diseases or cancers only to discover others. Our world, our lives are a mystery and it seems that the more we peer both inward and outward, the more we discover. It's an exciting time of life, a time where age has no bearing. It's almost, once could say, time-less.

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.