Oh, Pioids...

The power of addiction is strong, often overriding our normal impulses not with an urge, but with a seemingly unstoppable force. Ask any long-time cigarette smoker and you'll get a brief idea; and in lumping them all together it would almost appear that of the three main "addictions" that alcohol and cigarettes may seem trivial (as difficult as they might be) as compared to pain killers. Sometimes, the urge begins within 7 days, the prescribed drugs often prescribed and taken after a hip or knee surgery or other major operation; and for some, the stoppage (and effectiveness of the drugs) is not that big a deal. But for many, it is huge, as in wanting the pain killers all the time and soon suffering the symptoms of withdrawals if they're stopped (just ask the once-popular radio host, Rush Limbaugh, who once said on his show: There’s nothing good about drug use. We know it. It destroys individuals. It destroys families. Drug use destroys societies. Drug use, some might say, is destroying this country. And we have laws against selling drugs, pushing drugs, using drugs, importing drugs. And the laws are good because we know what happens to people in societies and neighborhoods which become consumed by them. And so if people are violating the law by doing drugs, they ought to be accused and they ought to be convicted and they ought to be sent up...Limbaugh was convicted of both drug use and fraud in illegally obtaining prescription drugs, but all charges were dropped when he agreed to enter rehab. As writer Tim Flannery wrote in his piece* about climate change, "Sometimes, it seems, threats to our future become so great that we opt to ignore them."

The struggle to overcome opioids and addiction to them and other drugs is real and reaches into virtually every corner of the U.S., something exemplified by TIME devoting an entire issue to the subject, and National Geographic putting it on it cover in 2017 and asking, "Why do human beings get addicted to substances and behaviors we know will harm us? What can new research tell us about addiction and the brain? Most important: Can what we're learning help more people recover?" The magazine begins the piece with this statistic: Every 25 minutes in the United States, a baby is born addicted to opioids...91 Americans die each day from opioid overdoes (updated figures show that the figure has now jumped to 145 Americans who die each day from opioid overdoses). The book Dreamland by Sam Quinones tried to explain some of this, jumping into rural areas with high unemployment and talking about the lucrative trade of legal drugs such as oxycontin; this from just 10 years ago: If you could get a prescription from a willing doctor --and Portsmouth (Ohio) had plenty of those-- the Medicaid health insurance cards paid for the prescription every month. For a three-dollar Medicaid co-pay, therefore, an addict got pills priced at a thousand dollars, with the difference paid for by the U.S. and state taxpayers. A user could turn around and sell those pills, obtained for that three-dollar co-pay, for as much as ten thousand dollars on the street.

One might want to partially blame the Sackler family who developed Oxycontin and apparently used deliberately deceptive advertising to get doctors to prescribe more of their drugs (such as using fictitious doctors names in testimonial flyers and cards and altering known lab results about the increased chance of addiction; one of their most well-known attorneys defending the family and their privately-held company --which unlike public companies, has no need to release background financials, policies or marketing results-- was Rudolf Giuliani, currently the lead attorney defending President Trump). The Sackler's company, Purdue Pharma, was advised of both the strength and the addictive possibilities with the opioid oxycodone used to replace the company's morphine pill, MS Contin...but it was cheap. In an extensive piece about the Sackler family in The New Yorker, writer Patrick Radden Keefe writes: Oxycodone, which was inexpensive to produce, was already used in other drugs, such as Percodan (in which it is blended with aspirin) and Percocet (in which it is blended with Tylenol). Purdue developed a pill of pure oxycodone, with a time-release formula similar to that of MS Contin (the "contin" in both drugs is an acronym for "continuous"). The company decided to produce doses as low as ten milligrams, but also jumbo pills --eighty milligrams and a hundred and sixty milligrams-- whose potency far exceeded that of any prescription opioid on the market. As Barry Meier writes, in "Pain Killer," "In terms of narcotic firepower, OxyContin was a nuclear weapon." Did (does) the family know that people were getting addicted to their drugs? After reading the article, one tends to think that they did (and do) but they have yet to put any money into helping people so addicted; indeed, as pressure mounts in the U.S. and more opioid deaths occur, the Sackler family is concentrating on moving their marketing model to Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, but under a different name, Mundipharma. Said writer Keefe: Part of Purdue's strategy from the beginning has been to create a market for Oxycontin -- to instill a perceived need by making bold claims about the existence of large numbers of people suffering from untreated chronic pain. As Purdue moved into countries like China and Brazil, where opioids may still retain the kind of stigma that the company so assiduously broke down in the United States, it's marketing approach has not changed...certain doctors who are currently flogging OxyContin abroad --"pain ambassadors," they are called-- used to be on Purdue's payroll as advocates for the drug in the U.S....In Mexico, Mundipharma has asserted that twenty-eight million people --a quarter of the population-- suffer from chronic pain.

McKesson, although known more as a distributor of such pills vs. being a manufacturer such as Purdue, settled in 2017 with the DEA (Drug Enforcement Adm.) for a once-record breaking $150 million; but as with Purdue and its own settlement with the DEA, both companies admitted no wrongdoing. The hiccup for them was the antiquated Controlled Substances Act which basically required distributors to note any "suspicious orders," say too many prescriptions going to one pharmacy or town or even a state. One example was the state of West Virginia where, in a five-year period from 2007 to 2012, some 760 million pain pills were shipped there, which converted to every man, woman, and child using 433 pills each. And despite a more detailed story by Fortune on the woes facing McKesson, the "big three" pill distributors (McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health) recently posted large gains in the stock market.

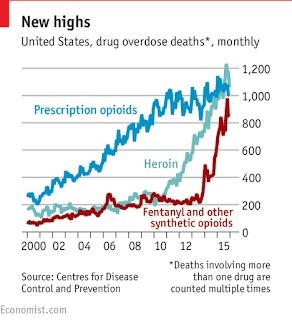

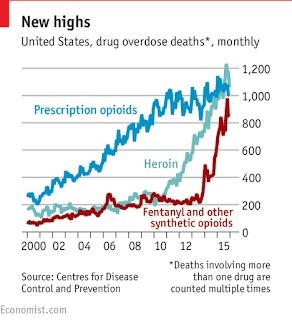

But for those in real pain, and now possibly addicted, legal relief is growing more and more expensive so many have turned to the cheaper (and available) heroin, easy to smuggle and unfortunately relatively easy to obtain. But there's another problem and that is the addition of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil. Both drugs are used for anesthesia with effects similar to morphine for pain but fentanyl is 50-100 times more powerful than morphine while carfentanil (primarily used on large animals such as elephants) is 10,000 times more powerful...and both are being mixed with the heroin on the streets. The result? A soaring level of overdose deaths. Said the CDC (Center for Disease Control), there is: ...a 15-year increase in deaths from prescription opioid overdoses (and) overdoses driven mainly by heroin and illegally-made fentanyl. Their statistics show a 15% increase of overdoses in the first 3/4 of 2016 vs. a year earlier (later year statistics are currently being compiled but will likely show a continuing increase as police reports show the rise of both heroin and fentanyl in their drug seizures).

But for those in real pain, and now possibly addicted, legal relief is growing more and more expensive so many have turned to the cheaper (and available) heroin, easy to smuggle and unfortunately relatively easy to obtain. But there's another problem and that is the addition of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil. Both drugs are used for anesthesia with effects similar to morphine for pain but fentanyl is 50-100 times more powerful than morphine while carfentanil (primarily used on large animals such as elephants) is 10,000 times more powerful...and both are being mixed with the heroin on the streets. The result? A soaring level of overdose deaths. Said the CDC (Center for Disease Control), there is: ...a 15-year increase in deaths from prescription opioid overdoses (and) overdoses driven mainly by heroin and illegally-made fentanyl. Their statistics show a 15% increase of overdoses in the first 3/4 of 2016 vs. a year earlier (later year statistics are currently being compiled but will likely show a continuing increase as police reports show the rise of both heroin and fentanyl in their drug seizures).

So what is the solution or solutions? The answers may come from places as far away as Tasmania and the Netherlands. And while many start-ups begin to tackle the difficult task of getting people off of such use (such as the introduction of testing devices such as TruNarc), sitting in the background are...you guessed it, the big drug manufacturers. Get them hooked on your pills, then get them hooked on getting off of your pills; already the market for treating some of the symptoms of opioids (such as constipation) is nearing the $3 billion mark. But the start-up market may beat those manufacturers to the punch with devices such as nerve stimulators (already awarded a contract by the Dept. of Defense) and buprenorphine. And there's educational work now being done on doctors and surgeons...what?? It's complicated, but happening...and next post, a quick summary of why there's hope that this crisis (but one not yet considered an emergency by our current administration, which would result in federal funding for a solution) might see brighter days and a possible decline.

*Flannery's piece, The Big Melt, appeared in The New York Review and is well worth reading despite him echoing the lament of journalist Seth Borenstein who said, "How many times can a journalist report on what is happening in the Arctic before it becomes so repetitive that people lose interest?" The effects on animals other than polar bears, waves of sea ice that can freeze musk oxen where they stand, and clathrates or as its more commonly known, "the ice that burns," are just some of the reporting he reviews. Here's just one excerpt from his piece, this on dedicated researcher Joel Berger's book Extreme Conservation: Investigating musk oxen killed by predators can be even more traumatic. One of the animals Berger collared was attacked by wolves. The radio collar pinged in a way that signified that the animal wearing it was dead. Unable to investigate right away, Berger arrived on the scene two days later and was astonished to find another carcass, beside which the rest of the herd waited "patiently, now for a full three days, as if somehow their presence will usher their two dead companions back to life." Berger leaned down to remove the collar: "A chunk of leg is gone. A hole punctures her abdomen. Part of the rump is eaten...The cow lies in the snow, edges melted away by the warmth of her decaying body. I push down on her throat. Her eyes open." Horrified, Berger realized that the mutilated creature was still alive -- indeed, it had been eaten alive for days. She tried to get to her feet. It took three shots to put her out of her misery. Whether one finds oneself apathetic or not, this --the effects of climate change-- is a big problem in the Arctic as warmer waters melt permafrost and glaciers, and allow mosquitos to make their way up sooner than normal, decimating herds of both caribou and musk oxen. This is not the time turn away...it's happening.

The struggle to overcome opioids and addiction to them and other drugs is real and reaches into virtually every corner of the U.S., something exemplified by TIME devoting an entire issue to the subject, and National Geographic putting it on it cover in 2017 and asking, "Why do human beings get addicted to substances and behaviors we know will harm us? What can new research tell us about addiction and the brain? Most important: Can what we're learning help more people recover?" The magazine begins the piece with this statistic: Every 25 minutes in the United States, a baby is born addicted to opioids...91 Americans die each day from opioid overdoes (updated figures show that the figure has now jumped to 145 Americans who die each day from opioid overdoses). The book Dreamland by Sam Quinones tried to explain some of this, jumping into rural areas with high unemployment and talking about the lucrative trade of legal drugs such as oxycontin; this from just 10 years ago: If you could get a prescription from a willing doctor --and Portsmouth (Ohio) had plenty of those-- the Medicaid health insurance cards paid for the prescription every month. For a three-dollar Medicaid co-pay, therefore, an addict got pills priced at a thousand dollars, with the difference paid for by the U.S. and state taxpayers. A user could turn around and sell those pills, obtained for that three-dollar co-pay, for as much as ten thousand dollars on the street.

One might want to partially blame the Sackler family who developed Oxycontin and apparently used deliberately deceptive advertising to get doctors to prescribe more of their drugs (such as using fictitious doctors names in testimonial flyers and cards and altering known lab results about the increased chance of addiction; one of their most well-known attorneys defending the family and their privately-held company --which unlike public companies, has no need to release background financials, policies or marketing results-- was Rudolf Giuliani, currently the lead attorney defending President Trump). The Sackler's company, Purdue Pharma, was advised of both the strength and the addictive possibilities with the opioid oxycodone used to replace the company's morphine pill, MS Contin...but it was cheap. In an extensive piece about the Sackler family in The New Yorker, writer Patrick Radden Keefe writes: Oxycodone, which was inexpensive to produce, was already used in other drugs, such as Percodan (in which it is blended with aspirin) and Percocet (in which it is blended with Tylenol). Purdue developed a pill of pure oxycodone, with a time-release formula similar to that of MS Contin (the "contin" in both drugs is an acronym for "continuous"). The company decided to produce doses as low as ten milligrams, but also jumbo pills --eighty milligrams and a hundred and sixty milligrams-- whose potency far exceeded that of any prescription opioid on the market. As Barry Meier writes, in "Pain Killer," "In terms of narcotic firepower, OxyContin was a nuclear weapon." Did (does) the family know that people were getting addicted to their drugs? After reading the article, one tends to think that they did (and do) but they have yet to put any money into helping people so addicted; indeed, as pressure mounts in the U.S. and more opioid deaths occur, the Sackler family is concentrating on moving their marketing model to Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, but under a different name, Mundipharma. Said writer Keefe: Part of Purdue's strategy from the beginning has been to create a market for Oxycontin -- to instill a perceived need by making bold claims about the existence of large numbers of people suffering from untreated chronic pain. As Purdue moved into countries like China and Brazil, where opioids may still retain the kind of stigma that the company so assiduously broke down in the United States, it's marketing approach has not changed...certain doctors who are currently flogging OxyContin abroad --"pain ambassadors," they are called-- used to be on Purdue's payroll as advocates for the drug in the U.S....In Mexico, Mundipharma has asserted that twenty-eight million people --a quarter of the population-- suffer from chronic pain.

McKesson, although known more as a distributor of such pills vs. being a manufacturer such as Purdue, settled in 2017 with the DEA (Drug Enforcement Adm.) for a once-record breaking $150 million; but as with Purdue and its own settlement with the DEA, both companies admitted no wrongdoing. The hiccup for them was the antiquated Controlled Substances Act which basically required distributors to note any "suspicious orders," say too many prescriptions going to one pharmacy or town or even a state. One example was the state of West Virginia where, in a five-year period from 2007 to 2012, some 760 million pain pills were shipped there, which converted to every man, woman, and child using 433 pills each. And despite a more detailed story by Fortune on the woes facing McKesson, the "big three" pill distributors (McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health) recently posted large gains in the stock market.

But for those in real pain, and now possibly addicted, legal relief is growing more and more expensive so many have turned to the cheaper (and available) heroin, easy to smuggle and unfortunately relatively easy to obtain. But there's another problem and that is the addition of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil. Both drugs are used for anesthesia with effects similar to morphine for pain but fentanyl is 50-100 times more powerful than morphine while carfentanil (primarily used on large animals such as elephants) is 10,000 times more powerful...and both are being mixed with the heroin on the streets. The result? A soaring level of overdose deaths. Said the CDC (Center for Disease Control), there is: ...a 15-year increase in deaths from prescription opioid overdoses (and) overdoses driven mainly by heroin and illegally-made fentanyl. Their statistics show a 15% increase of overdoses in the first 3/4 of 2016 vs. a year earlier (later year statistics are currently being compiled but will likely show a continuing increase as police reports show the rise of both heroin and fentanyl in their drug seizures).

But for those in real pain, and now possibly addicted, legal relief is growing more and more expensive so many have turned to the cheaper (and available) heroin, easy to smuggle and unfortunately relatively easy to obtain. But there's another problem and that is the addition of synthetic fentanyl and carfentanil. Both drugs are used for anesthesia with effects similar to morphine for pain but fentanyl is 50-100 times more powerful than morphine while carfentanil (primarily used on large animals such as elephants) is 10,000 times more powerful...and both are being mixed with the heroin on the streets. The result? A soaring level of overdose deaths. Said the CDC (Center for Disease Control), there is: ...a 15-year increase in deaths from prescription opioid overdoses (and) overdoses driven mainly by heroin and illegally-made fentanyl. Their statistics show a 15% increase of overdoses in the first 3/4 of 2016 vs. a year earlier (later year statistics are currently being compiled but will likely show a continuing increase as police reports show the rise of both heroin and fentanyl in their drug seizures). So what is the solution or solutions? The answers may come from places as far away as Tasmania and the Netherlands. And while many start-ups begin to tackle the difficult task of getting people off of such use (such as the introduction of testing devices such as TruNarc), sitting in the background are...you guessed it, the big drug manufacturers. Get them hooked on your pills, then get them hooked on getting off of your pills; already the market for treating some of the symptoms of opioids (such as constipation) is nearing the $3 billion mark. But the start-up market may beat those manufacturers to the punch with devices such as nerve stimulators (already awarded a contract by the Dept. of Defense) and buprenorphine. And there's educational work now being done on doctors and surgeons...what?? It's complicated, but happening...and next post, a quick summary of why there's hope that this crisis (but one not yet considered an emergency by our current administration, which would result in federal funding for a solution) might see brighter days and a possible decline.

*Flannery's piece, The Big Melt, appeared in The New York Review and is well worth reading despite him echoing the lament of journalist Seth Borenstein who said, "How many times can a journalist report on what is happening in the Arctic before it becomes so repetitive that people lose interest?" The effects on animals other than polar bears, waves of sea ice that can freeze musk oxen where they stand, and clathrates or as its more commonly known, "the ice that burns," are just some of the reporting he reviews. Here's just one excerpt from his piece, this on dedicated researcher Joel Berger's book Extreme Conservation: Investigating musk oxen killed by predators can be even more traumatic. One of the animals Berger collared was attacked by wolves. The radio collar pinged in a way that signified that the animal wearing it was dead. Unable to investigate right away, Berger arrived on the scene two days later and was astonished to find another carcass, beside which the rest of the herd waited "patiently, now for a full three days, as if somehow their presence will usher their two dead companions back to life." Berger leaned down to remove the collar: "A chunk of leg is gone. A hole punctures her abdomen. Part of the rump is eaten...The cow lies in the snow, edges melted away by the warmth of her decaying body. I push down on her throat. Her eyes open." Horrified, Berger realized that the mutilated creature was still alive -- indeed, it had been eaten alive for days. She tried to get to her feet. It took three shots to put her out of her misery. Whether one finds oneself apathetic or not, this --the effects of climate change-- is a big problem in the Arctic as warmer waters melt permafrost and glaciers, and allow mosquitos to make their way up sooner than normal, decimating herds of both caribou and musk oxen. This is not the time turn away...it's happening.

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.