A Flood...

Phonetically, one would think that the word flood would be spelled "flud" but then throw in an "i" and that word would become "fluid;" or take away the "l" from flood and the word would become "food;" change the last letter from "l" to "r" and it becomes "floor," which rhymes with the giant corporation Fluor but is pronounced totally different from its dyslexic spelling of "flour." Such are the variances of the English language, it's changing patterns and pronunciations perhaps overshadowed by the vocal intonations so necessary when speaking Mandarin in which a single inflection can entirely alter a word's meaning. Hmm, this is likely a "flood" of information, but is perhaps indicative of just how a flood has come to be defined...unexpected, overwhelming, disruptive and often devastating. To awaken to a broken washer line and a flooded floor (or in our area, a basement or cellar) is one thing, but to have your entire home or yard or streets turned into a river, one which washes everything (possibly including you) away, is quite another.

According to National Geographic, floods: ...are among Earth's most common --and most destructive-- natural hazards...But flooding, particularly in river floodplains, is as natural as rain and has been occurring for millions of years. Famously fertile floodplains like the Mississippi Valley in the American Midwest, the Nile River valley in Egypt, and the Tigris-Euphrates in the Middle East have supported agriculture for millennia because annual flooding has left millions of tons of nutrient-rich silt deposits behind. So there's that side. But of course, when you are poor and your homes are made of mud, and you've endured days and days of rain which have weakened or already destroyed your walls, and then a flood arrives, it is a true disaster. Rescue workers are still working to gain access into areas of Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Milawi after cyclone Idai hit its coastline, bringing not only vast amounts of ocean water and overflowing rivers, but powerful winds that ripped apart buildings and overturned trucks. And the numbers are staggering, said a report from Vox: In Mozambique, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that 242 people have died (and the numbers are likely to continue to rise). Some 1,500 are injured, and 65,000 people are living in shelters...In Zimbabwe, the UN reports, 102 people are dead and 217 are missing. An additional 200,000 people in the Chimanimani district of Zimbabwe (where the storm hit) are believed to need urgent food aid over the next few months, the Guardian reports. In Malawi, 56 people are reported dead and 82,700 people are displaced. The death toll is expected to surpass a thousand as workers continue to rescue people still stranded on roofs or trees; and as the water begins to recede there is the mud, the trapped sewage, the cholera likely waiting, the lack of food, the lack of clothing, the lack of pretty much anything. This is a poor section of the world, a forgotten and less-known area, off the beaten track and when nearly 4 meters of ocean moved inland, there was little people (much less the animals) could do.

The flood situation in Nebraska and other parts of the central Midwest in the U.S. is proving equally devastating as storage bins of harvested crops now face mold and damp, cattle and pigs are drowned or missing, bridges and roads are collapsed...and the winter snow melt is still to come. Already weakened levees meant to channel the rising waters along the river and into the ocean are breaking from the stress; and worse comes the realization that this might be a foretelling of the new normal in coming years. Ocean waters are rising as polar ice melts, the waters' air temperature is warmer and slows both the currents and the paths of storms causing the rains and runoffs into rivers to continue for far longer with little movement once on land; often there is nowhere for the water to go except further onto the land. Such are the new predictions with these floods and monsoons and heavy melts becoming ever larger. But imagine that instead of a home or farm flooding it's one of the command centers for the U.S. military and you were struggling to save computers and satellite data, much less aircraft and heavy equipment.

Much of this has happened before, even in Mozambique which was hit equally hard in 2000 and 2017. But even a quick glance at a flood timetable (taking into account better record keeping and that only a fifth of this century has passed) and it would appear that nature is adjusting its water distribution regardless of our barriers. All of this brought to mind my own experience back in the 80s when I lived in an area north of San Francisco. Torrential rains had overflowed small rivers and mudslides washed away homes and patches of woods. As I volunteered to help a family dig out I was but one of thousands pitching in, encountering people from all walks of life including soil engineeers who told me that the hills of Marin, these "mountains" where I was so used to living and walking in at the time, were relatively new, destined to become the next Sierra Mountains as they continued their land movement inward; the soils hadn't had time to compact, to hold firmly to the steep rock base underneath, the earth below this area prone to restlessness as the San Andreas fault would prove now and then; the famed Tomales Bay next door (known in the area for its oyster beds) was formed when the fault created a rift that let in the ocean. The engineers pointed out that the sand which we were bagging* was actually crushed granite, remnants of that glacial-like movement of the continental plates moving inland. It was geologic speak of course, their time frames measured in centuries and eons; but even as other geologist and hydrologists looked at engineering maps from the early 1900s, they could see that old natural waterways were ignored or considered "hundred year" paths and that building a highway or a building over it was okay (at the time, a portion of the highway in Sausalito had washed away which caused city planners to view the earlier maps to determine what had happened).

What struck me about my earlier writing (this was the storm of 1982, although the area experienced pretty much the same devastation this year) was the reality of being there. witnessing mud lines haflway up tree trunks, the logistics of ensuring that individual gas and water lines had been shut off (often in major disasters, utility companies will decide to just close off the main lines as a precaution), the loads of gawkers just wanting to "see" the damage but not help (most were turned away and kept to the outskirts), the once-beautiful Holly Tree Inn, so named for its grove of said trees, now looking"...closer to the tangled river's end it was. Cut tree sections --three and four feet in diameter-- were everywhere. The endless wall of mud that arrived first broke through the inn's garage, filling it with four feet of concrete-like mud...it took seven hours, six people and a Caterpillar tractor to remove the mass from the small area. The inn itself was ironically saved by Tom's (he and his wife Diane owned the inn) car which had effectively done what sandbags had failed to do -- having floated out of the driveway, it had wedged against the house and diverted the water around the front. Two guests at the inn watched helplessly as their cars floated away with Diane's car, settling in the muddy swamp some 200 yards farther down...boulders the size of large tractor tires had arrived outside for an extended stay. But within days, unless you lived there, the storm and the mud and rebuilding was old news, the radio stations already directing people to other areas more desperate for help, said my piece. That and the leaving, the humility of those being helped still saying that others had it worse and witnessing "...the weak, but honest, smiles of thanks from countless people simply trying to recover."

The waters in most areas are already receding (in the Midwest, the urgency is to rebuild what they can before the snows melt and send even more water in the already stressed diversion channels and rivers). And even in Mozambique and the other African areas affected, even as people cry out for food and water and an extra blanket or a piece of clean clothing, the event is mostly forgotten. Somehow it'll be taken care of, somehow the rescue work will continue, somehow the water and fences and homes will be rebuilt, somehow their lives will go on...perhaps not as quickly as here in the U.S., but somehow (Puerto Rico, a commonwealth of the U.S. --think colony of sorts-- took over a year to have its electricity fully restored, this despite Puerto Ricans being U.S. citizens; on a side note, four U.S. states are also commonwealths). But then think back to our own floods, those true floods of emotion, those difficult times in one's life where something traumatic has happened -- surviving an accident or drug overdose, facing the loss of a child or sibling, being robbed or coming near to being bankrupt, blowing out your knee or surviving cancer, being raped or encountering a sexual assault; the list could be endless and be as simple as an intimidating encounter. The emotions that came, slowly, ever so slowly perhaps, began to recede. But with that we may have noticed that even faster to recede was the interest by others. Acquaintances and neighbors first, then a few friends, then some family, and eventually our own mind. But inside we're all aware that the damage remains, etched out somewhere in the our mind's archives, perhaps safely locked away for a reason and waiting only for a valid reason that it needs to be reopened and explored. Our own floods can be just as devastating and crippling as those that have hit others, both physically and emotionally. But what we may find more shocking is our discovery at just how soon the world moves on and how quickly we begin to discover how strong or weak we are inside ourselves...and where our frailties and our strengths rest.

*Interesting thing about sand bagging, a back-breaking job as wet mud or sand is shoveled into what seems an endless amount of bags...in the article I wrote about my experience and mentioned that we were building a three-foot high wall of bags (another storm was due the next day) and we would: ...fill a bag three-quarters full, fold the flap, pile on the next bag. Mud, now a necessary "glue," went between the piled bags to patch them together. One bag, fifty bags, more helpers, more bags. The inn (where we were working) became a barracks, an old war effort to fend off further damage from the enemy, the mud. It all sounds pretty basic, eh? Even now. Fill, fold, stack, repeat. But later in the piece I wrote: Our sandbagging efforts increased (though the fire marshals corrected our method of stacking -- sealed end toward the water, bags half full, flaps interlocking.) For those of you facing this possibility of building a sandbag wall or looking to build a sandbag dyke in advance, here's an accurate guide about the procedure...

|

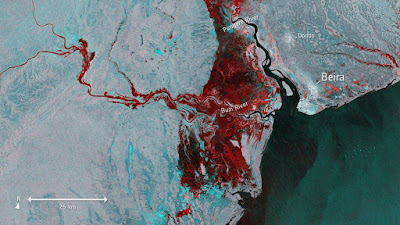

| Flooded Mozambique area 80 x 15 miles wide. Photo: European Space Agency |

The flood situation in Nebraska and other parts of the central Midwest in the U.S. is proving equally devastating as storage bins of harvested crops now face mold and damp, cattle and pigs are drowned or missing, bridges and roads are collapsed...and the winter snow melt is still to come. Already weakened levees meant to channel the rising waters along the river and into the ocean are breaking from the stress; and worse comes the realization that this might be a foretelling of the new normal in coming years. Ocean waters are rising as polar ice melts, the waters' air temperature is warmer and slows both the currents and the paths of storms causing the rains and runoffs into rivers to continue for far longer with little movement once on land; often there is nowhere for the water to go except further onto the land. Such are the new predictions with these floods and monsoons and heavy melts becoming ever larger. But imagine that instead of a home or farm flooding it's one of the command centers for the U.S. military and you were struggling to save computers and satellite data, much less aircraft and heavy equipment.

Much of this has happened before, even in Mozambique which was hit equally hard in 2000 and 2017. But even a quick glance at a flood timetable (taking into account better record keeping and that only a fifth of this century has passed) and it would appear that nature is adjusting its water distribution regardless of our barriers. All of this brought to mind my own experience back in the 80s when I lived in an area north of San Francisco. Torrential rains had overflowed small rivers and mudslides washed away homes and patches of woods. As I volunteered to help a family dig out I was but one of thousands pitching in, encountering people from all walks of life including soil engineeers who told me that the hills of Marin, these "mountains" where I was so used to living and walking in at the time, were relatively new, destined to become the next Sierra Mountains as they continued their land movement inward; the soils hadn't had time to compact, to hold firmly to the steep rock base underneath, the earth below this area prone to restlessness as the San Andreas fault would prove now and then; the famed Tomales Bay next door (known in the area for its oyster beds) was formed when the fault created a rift that let in the ocean. The engineers pointed out that the sand which we were bagging* was actually crushed granite, remnants of that glacial-like movement of the continental plates moving inland. It was geologic speak of course, their time frames measured in centuries and eons; but even as other geologist and hydrologists looked at engineering maps from the early 1900s, they could see that old natural waterways were ignored or considered "hundred year" paths and that building a highway or a building over it was okay (at the time, a portion of the highway in Sausalito had washed away which caused city planners to view the earlier maps to determine what had happened).

What struck me about my earlier writing (this was the storm of 1982, although the area experienced pretty much the same devastation this year) was the reality of being there. witnessing mud lines haflway up tree trunks, the logistics of ensuring that individual gas and water lines had been shut off (often in major disasters, utility companies will decide to just close off the main lines as a precaution), the loads of gawkers just wanting to "see" the damage but not help (most were turned away and kept to the outskirts), the once-beautiful Holly Tree Inn, so named for its grove of said trees, now looking"...closer to the tangled river's end it was. Cut tree sections --three and four feet in diameter-- were everywhere. The endless wall of mud that arrived first broke through the inn's garage, filling it with four feet of concrete-like mud...it took seven hours, six people and a Caterpillar tractor to remove the mass from the small area. The inn itself was ironically saved by Tom's (he and his wife Diane owned the inn) car which had effectively done what sandbags had failed to do -- having floated out of the driveway, it had wedged against the house and diverted the water around the front. Two guests at the inn watched helplessly as their cars floated away with Diane's car, settling in the muddy swamp some 200 yards farther down...boulders the size of large tractor tires had arrived outside for an extended stay. But within days, unless you lived there, the storm and the mud and rebuilding was old news, the radio stations already directing people to other areas more desperate for help, said my piece. That and the leaving, the humility of those being helped still saying that others had it worse and witnessing "...the weak, but honest, smiles of thanks from countless people simply trying to recover."

The waters in most areas are already receding (in the Midwest, the urgency is to rebuild what they can before the snows melt and send even more water in the already stressed diversion channels and rivers). And even in Mozambique and the other African areas affected, even as people cry out for food and water and an extra blanket or a piece of clean clothing, the event is mostly forgotten. Somehow it'll be taken care of, somehow the rescue work will continue, somehow the water and fences and homes will be rebuilt, somehow their lives will go on...perhaps not as quickly as here in the U.S., but somehow (Puerto Rico, a commonwealth of the U.S. --think colony of sorts-- took over a year to have its electricity fully restored, this despite Puerto Ricans being U.S. citizens; on a side note, four U.S. states are also commonwealths). But then think back to our own floods, those true floods of emotion, those difficult times in one's life where something traumatic has happened -- surviving an accident or drug overdose, facing the loss of a child or sibling, being robbed or coming near to being bankrupt, blowing out your knee or surviving cancer, being raped or encountering a sexual assault; the list could be endless and be as simple as an intimidating encounter. The emotions that came, slowly, ever so slowly perhaps, began to recede. But with that we may have noticed that even faster to recede was the interest by others. Acquaintances and neighbors first, then a few friends, then some family, and eventually our own mind. But inside we're all aware that the damage remains, etched out somewhere in the our mind's archives, perhaps safely locked away for a reason and waiting only for a valid reason that it needs to be reopened and explored. Our own floods can be just as devastating and crippling as those that have hit others, both physically and emotionally. But what we may find more shocking is our discovery at just how soon the world moves on and how quickly we begin to discover how strong or weak we are inside ourselves...and where our frailties and our strengths rest.

*Interesting thing about sand bagging, a back-breaking job as wet mud or sand is shoveled into what seems an endless amount of bags...in the article I wrote about my experience and mentioned that we were building a three-foot high wall of bags (another storm was due the next day) and we would: ...fill a bag three-quarters full, fold the flap, pile on the next bag. Mud, now a necessary "glue," went between the piled bags to patch them together. One bag, fifty bags, more helpers, more bags. The inn (where we were working) became a barracks, an old war effort to fend off further damage from the enemy, the mud. It all sounds pretty basic, eh? Even now. Fill, fold, stack, repeat. But later in the piece I wrote: Our sandbagging efforts increased (though the fire marshals corrected our method of stacking -- sealed end toward the water, bags half full, flaps interlocking.) For those of you facing this possibility of building a sandbag wall or looking to build a sandbag dyke in advance, here's an accurate guide about the procedure...

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.