Fill 'Er Up...Buster

The other night found my wife and me gathered at a dinner table with friends; all of us had received our 2nd dose of the vaccine and the relaxation emanating at the gathering was noticeable. As with so many other people who were watching the weather warm and the flowers emerging from the ground, there was a feeling of comfort as if just having the ability to see everyone's body language added to the interruptions and lively conversations and the clinking of glasses in a toast; it was all just showing us how much of the "everyday" we had missed, and how much we had tired of Zoom and other "online" talks. Make no mistake, each of us had been overly careful in the past 10 months or so, almost paranoid-careful; we isolated or met with a neighbor once a month (or less) and made sure we kept our distance and had plenty of masks in the car, along with hand sanitizer and a cornucopia of a other viral-cleansing products. But even with all of that, the risk of getting infected remained a big unknown. Just ask the 563,000+ people in the U.S. (and 3+ million worldwide) who are no longer here due to the virus. Besides, we could all be lumped into the "older" category at this gathering which added to our caution and also added to our enjoyment of a fabulous home-cooked dinner.

What emerged from that evening was a banter that included questions to my wife asking her to explain some British words which came almost as slang to the rest of us and our foreign ears. Knickers in a twist, bugger off, pissed (with means one having a bit too much to drink, and not that one is angry), put the kettle on. It reminded me of my days in Hawaii and having to explain some of the "pidgin" I used as a child (a majority of it long forgotten). Howzit brah? Such questions have led to a variety of books which try to explain such localized language and idioms, but few proved as extensive as the book by Shirley and Harold Kobliner who decided that they would compile a list of phrases they or their friends has personally heard, their one rule being that they wouldn't refer to other already-written books or the Internet but only the phrases personally heard by families and friends. The result was a 10-year project that yielded 11,000 expressions (the author's wife passed away before the book was completed). It reminded me of a tea towel I spotted that had the phrase: Respect your parents...they got through school without Google.

Here's part of the book's introduction: We use expressions all the time, often without much thought. When you feel sick, you're under the weather; when you feel great, you're on top of the world! If you don't speak up, it could be that the cat's got your tongue, or maybe it's just a frog in your throat. You may be fine with half a loaf, or you may insist on the whole enchilada. No matter if you're a smart cookie or a tough one, you --and most everyone you know-- has a veritable smorgasbord of expresions stored deep in your brain. But expressions are more than just words; they tell a story of who you are, where you lived, and when you grew up. Someone who says a friend is all hat and no cattle is likely from a different neck of the woods than the person who asks What am I, chopped liver? Expressions also offer a clue as to when you came of age: if you ask for the skinny on a rumor you hear, you're almost certainly longer in the tooth than if you ask someone to spill the tea.

"Out with the old, in with the new" was a phrase I grew up with, although I'm not sure where or when I first heard it (and actually can't remember it being used that often). But it seemed to apply as I browsed though my ever-growing pile of magazines and "saved" articles to read, not to mention the backlog of books I once considered too "precious" to simply discard (my library was having a "sale" and how could I resist not getting even more books?). Many of the once-relevant stories in the magazines, especially those concerning politics or economies, proved to be old news now that they were months old. Sometimes they were correct, and other times they weren't; but for the most part the expectations and predictions turned out to be just elaborated opinions in the end, any actual and dry reporting separating itself like cream from other pieces that simply proved to be educated analyses. The "breaking news" of those times was no longer so exciting. The world had continued to move on.

|

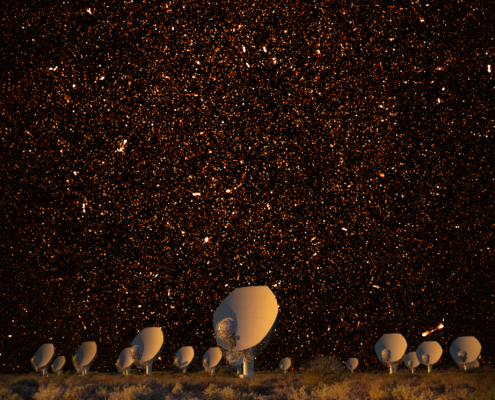

| Collection of galaxies photo: SARAQ, NRAQ/AUI/NSF |

Back in the day when the Roman Empire was in decline, people made a concerted effort to save pieces of its accomplishments; among these people were Irish monks who, wrote Tom Cahill: ...tirelessly copied Greek, Latin, and Christian manuscripts, starting in the fifth century, while archives on the European continent were lost forever to Visigoths. Added a piece in Wired, "The primitive bells of the doomsday-cult monks were called chuigs; cluig, with various spellings, is one source of the modern word clock." Doomsday, there's another one of those words. "The end is near" has been around since, well, the beginning.

But dig deeper into that photo taken by the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (as their site says: ...the largest radio telescope ever built...in South Africa and eight other African countries [and Australia, and]...exceeding the image resolution quality of the Hubble Space Telescope by a factor of 50 times) and you'll be surprised to learn that those are not stars you're looking at, but entire galaxies, some long gone. Added Discover: As astronomers have studied greater numbers of galaxies over the past few decades, they’ve discovered many things, but one that is impossible to ignore is that the universe is incredibly large. If you look at a galaxy in your telescope’s eyepiece tonight, the photons striking your eye have been traveling at the fastest speed there is — 186,000 miles per second (300,000 kilometers per second). Nonetheless, they have taken 2.5 million years at that velocity to reach us from the Andromeda Galaxy. And that object is nearly on our cosmic doorstep.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs wrote an essay for Sierra describing her feelings as she tried to picture the nebula NGC 1499, a red-wavelength nebula shaped like the state of California but nestled about 1000 light-years away: By the time you read this, that news will be old. The California Nebula is 1,000 light-years away, which means that even if I could see it, I would be late, vaguely observing what the emissions from the bright star Xi Persei looked like a thousand years ago. Is it still as bright or as dull? What is it emitting today? I will not live to know...What would it take to see the planet we are on beyond our own mythology of need? Or maybe more important, 100 years from now, 1,000 light-years from here, what will they say about what we emitted, our nebulous state of ionization? How diffuse and how perceptible? How red?

Jump over to the somewhat chilling issue-long excerpt* of the book 2034 which appeared in Wired, a scenario where communications are knocked out in wargames, to devastating consequences (picture missiles, jets, and even aircraft carriers staring at blank screens, their navigation and other systems disabled). This forces them to rely on "older" technology (remember UHF and VHF?), which one officer explains to his commander: "We're searching for long-delayed echoes, ma'am, LDEs. When you transmit an HF frequency, it loops around the earth until it finds a receiver. On rare occasions, that can take a while and you wind up with an echo." "How long of an echo?" asked Hunt (the female captain). "Usually only a few seconds," said Quint..."Old salts I served with said that in these waters they'd picked up conversations from fifty or even seventy-five years ago," explained Quint..."There's lots of ghosts out here, ma'am. You just got to listen for 'em."

An interesting piece on extraterrestrial languages appeared in the London Review of Books, and was simply titled, "We're not talking to you, we're talking to Saturn." It explained the effort to change our SETI broadcasts to space to METI.** Sounds like gobbly goop but government funding for SETI was cut back in 1993 and a host of other types of messaging have stepped in to take its place. SETI still exists, its site adding this: Until now, SETI researchers have not been very interested in broadcasting. The reasons for this are several. To begin with, we are a technologically young civilization. We have had radio for a hundred years or so, but there are surely societies that have possessed the ability to send high-powered signals for tens of thousands, if not millions, of years. Consequently, since we are the new kids on the technology block, it may behoove us to listen first.

So listen up, (another phrase I often heard as a child)...it's good advice. Back in the day one would drive into a gas (not service) station and tell the attendant, "fill her up," a reference for you to casually stay in your car and relax as the windshield was hand-cleaned (no Squeegees in those days) while you "gassed up," and premium gas was called "ethyl." Then came a cost for that service (full-serve and self-serve) and eventually, here we are at pre-pay and do-it-yourself facilities. Contracts and stock trades are done on phones, laptop transactions disappearing almost as quickly as the days of sending a fax. Times are changing, buster (buster was another common if somewhat demeaning phrase back then, although there were such personalities as Buster Keaton and Buster Brown shoes).

Which brought me to a piece in Bloomberg Businessweek about Piecework, a "gourmet" puzzle company that is seeing growing pains as its sales continue to skyrocket (its sales grew 910% in 3 months in early 2020). It reminded me of an article I published ages ago (as in 40 years ago), one about the increasing demand for puzzles...I was thrilled to interview professors who dealt with perceptions and psychology, as puzzles began changing from images to solid colors, odd shapes, and even 3-dimensions, all an effort to appease the increasing demand of their audience who wanted more and more difficulty (competitions saw 1000-piece puzzles --blank and with ever-new "cuts"-- solved in under an hour). Even back then the conclusions were simple: puzzles were non-competitive, and age and time didn't matter. A family could work together or separately and at any time, coming and going. A piece here, a piece there. It didn't really matter (one professor noted that the only other "game" she could think of that fit that category was in tossing the Frisbee). People could work together in silence or talk just randomly without looking up, just letting their minds wander as they searched for the next piece that would fit. It was an interesting period of time, a time of relaxation and a time when all seemed okay in the world, "our" world. It was life, reflected kindly in a nod of the head, a twinkle in the eye, even in the clink of a glass...

Addendum: Without getting too technical and without trying to spoil the mood, a current ongoing debate here in the U.S. regards the use of the fillibuster, a political definition saddled with cloture and reconciliation. The filibuster has been used extensively by both parties but is now being considered on the cusp of elimination as states step in to possibly override federal regulations (grid lock is another term often heard regarding Congressional legislation). Said The Washington Spectator: We also need to fix voting rights and election systems in 2021 because things will likely only get worse in 2022. Researchers at the Brennan Center for Justice have established that lawmakers in 43 states have endorsed more than 250 bills that would make it harder for citizens to vote—over seven times the number of voter suppression bills introduced around this time last year...In Arizona, which Trump lost, there is a proposed bill to give legislators the power to overrule state election officials and the popular vote. In Pennsylvania, another state Trump lost, Republican lawmakers have introduced 14 voter suppression measures.

*When, if ever, have you seen a magazine devote an entire issue to a book? In this case, Wired felt that it was necessary to "warn" readers of our apparent over-reliance on satellite and internet communications. The excerpt (which highlighted the possible conflict) was riveting, but on peeking at reviews by others who have read the entire book, the ratings were mixed, some saying that little actual technical detail was provided and the that the story drifted off a bit. Nonetheless, the co-authors are no slouches, one having served five tours in Iraq and Afghanistan (as well as in the White House), and the other being an Admiral who served as "supreme allied commander of NATO from 2009-2013, and led fleets of destroyers and carriers. It all added a bit more credence to their insights and imagined future vs. coming from a pair of writers attempting to write yet another best-seller.

**The SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) is but one of many such METI (Messaging) efforts to communicate with other life, although as the article asked, "How do you communicate with a planet-sized slime with ESP that eats electricity?" SETI was beamed or tuned at 1420 MHz, the "radiation frequency of neutral hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe..." but getting through our atmosphere is rather difficult. As the article mentioned "...messages at these frequencies would be impeded by the Earth's atmospheric gases, making it impossible for us to receive them. Our planet may be constantly being pelted by alien messages that never make it through the wall of gas." METI, one of many types of messaging efforts, sends out blips or bitrates of messaging, along with a "clock" somewhat deciphering the data. If you're confused, consider yourself in good company...each of these efforts hope to reach a more intelligent life form beyond our planet, although the article ended with this note: Like AI (Artificial Intelligence) research, Meti has the potential to expose us to a vastly superior intelligence that could either solve all our problems or obliterate us entirely. Historically, encounters between technologically better and worse-off societies haven't worked out well for the worse-off.

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.