Memoirs...Mem-noirs

My thoughts swirled like a whirlwind of tiny dust particles caught in a beam of sunlight when it hits the living room floor...random, floating, too small to grasp or capture, plentiful. Much of this was because I had been sporadically reading a number of those Best American series of books. It's something I do every three years or so, order about 8 or 10 of the books from past years (in this case from 2017 to 2020) and see what I may have missed. New (to me at least) was the series Best American Food Writing (their other collections span everything from sports to science & nature, short stories to mysteries, travel to poetry, and more, even comics and non-required reading). As before, I found it dazzling to read just from the few I had ordered. The writing was as terrific as in past years, and reminded me of the difficult task each editor faces when honing down the list from the hundreds and hundreds of submitted published pieces, to a smaller list of just a hundred or so, and then making the final decision of picking just 20 or so to include in the finished books...and that was from just whatever year was being considered. Come next year, start over...

Here's how Glenn Stout, long-time series editor for the Best American Sports Writing series put it in 2018: A number of annual "best" lists are put together in this field, ranging from those accumulated by sources such as Longreads, Longform, and The Sunday Long Read to lists curated by individuals and outlets to the annual industry awards, sponsored by organizations like the American Society of Magazine Editors, the Canadian Society of Magazine Editors, the Associated Press Sports Editors, the City and Regional Magazine Association, and others...I look at all these lists, primarily to make sure I don't miss anything, read virtually all of them (as well as thousands of others on my own and through submissions:, and rarely find much consensus: each audience has its own definition of "best," and only a scant few individual stories each year are cited by more than one or two of these lists. At best, like this volume, they're a rough guide, nothing more. At the same time, many equally fine stories slide through the cracks, whether excluded by gatekeepers or simply overlooked and never even considered for recognition...In a business that is too often harsh and unfair, I feel a responsibility to let these writers know that their work isn't disappearing into the void and that someone us paying attention.

I had never heard of Longreads or Longform or what is likely quite a number of other such groups and editors working diligently to try and expose the stories and writers who may have this one shot to show the world what may be a life-changing, or certainly thought-changing, bit of writing. Here was one which appeared in Runner's World about Shannon Farar-Griefer and her running the annual Badwater race, a gruelling 135-mile task that starts below sea level at Death Valley and eventually climbs halfway up Mt. Whitney (race officials apparently felt that the original ending climb to the summit was far too difficult so they changed the end point to an elevation 6000' lower): At 9:41 a.m., on July 27, 2001, Shannon Farar-Griefer jogged through a knot of cheering people in a pine forest clearing at the base of California’s Mt. Whitney. She had been running—and limping, puking, cramping, and crying—for 135 miles. After almost 52 hours, her feet were covered with oozing blisters. Five toenails were black...All of the 71 Badwater 135 ultramarathon competitors had started at Death Valley—at 280 feet below sea level, the lowest point in North America—and the 55 finishers (Shannon was 38th) had ended the race here, among the pines, at 8,300 feet. But Shannon wanted to keep going. Before race organizers, park officials, and, one imagines, commonsense concerns about death and liability conspired to shorten the course in 1990, Badwater had finished at the summit of Mt. Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States. Some runners groused about overcautious race directors; Shannon, though, had her own idea. Now that she had finished the current course, she wanted to finish the former one. She intended to climb Mt. Whitney, some 11 miles farther and 6,100 feet higher than where she stood (after 3 hours of sleep, she would indeed complete the run to the top, returning 24 hours later)...she told her husband to get the boys in the car. She’d meet them later. She needed to do something. Ben was wailing: Why couldn’t she stop?...She watched her family drive away, then yanked three blackened toenails off her right foot, two off her left. She wanted to “double” the route—the entire original route—which meant that she had 135 more miles to go. She ran back toward Death Valley, back to where she had started.

What drives a person like that? In fact, what drives editors to plow through submission after submission to present such stories once again (each book often lists in the back the "notable" articles that had to be shed from being reprinted in the books, but which they felt were worth looking at). Would I have looked at Runner's World to find that story (no), or Outside, or Orion? Was I even aware of such a number of magazines were attracting such writing, much less that writers were covering such stories (and that happened to only be the "sports" collection, a subject I'm not that interested in; truth be told, I skipped most of the basketball and football stories...gasp). What awaited me were the science and food and travel books...and baggy eyes.

On the other hand, the next year editor Stout (again from the Sports edition) wrote this: It's no secret, to either readers or writers, that the entire writing industrial complex is in trouble as regards not just sports writing but just about every kind of writing that makes use of letters, sentences, and the occasional paragraph. Jobs are scarce, layoffs have spread like measles among the unvaccinated, and print and online publishers close or merge into the dim-witted mists of capital reorganization every day. The few that remain not only publish less written work every year but often treat it like an enormous bother. Somehow writing itself has become the greatest impediment to the reigning business model, which measures success in IPOs, an office fridge full of double IPAs, and a summer tiny house...Not only are there fewer jobs --by some estimates in the last decade half of all journalism jobs have disappeared-- but already stagnant pay is going down, and fast. Finalists for the National Magazine Award have asked if I know where they might be able to pitch a story and get paid in cash. I know of legacy outlets that now pay only $100 for stories that run thousands of words, often make the writer wait many, many months for that, and cut a check only after the writer has expended more pretty-please words begging for payment than they used in the original story.

|

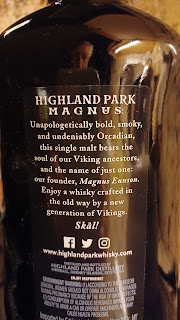

| A tasty ancestral nightcap... |

Author Taussig had recently written a piece on some of the feelings and worries of flying as a disabled person, another essay which will not only give you something to think about, but it well worth reading on its own. Said Taussig on her webpage: I am a Kansas City writer who lives in a very small, very old house with my fussy family of tenderhearted snugglers. I’ve spent most of my life immersed in the world of writing and reading –as a student, teacher, and human person– because I believe that words and stories matter. I am interested in the powerful connection between the cultural narratives we tell and the world we live in, from physical spaces and economic opportunities to social roles and interpersonal relationships. She's not alone. Pianist Brad Mahldau pasted these words on the cover of one of his recent albums: Suite April 2020 is a musical snapshot of life the last month in the world we've all found ourselves. I've tried to portray on the piano some experiences and feelings that are both new and common to many of us. In "keeping distance", for example, I traced the experience of two people social distancing, represented by the left and right hand -- how they are unnaturally drawn apart, yet remain linked in some unexplainable, and perhaps illuminating way.

Shifting lives, shifting climates. Here's a glimpse of writing by Mark Arak on the almond/ pomegranate/mandarin orange family empire sucking the water out of California (from the 2019 Food collection): The big-rig drivers are cranky two ways, and the farmworkers in their last-leg vans are half-asleep. Ninety-nine is the deadliest highway in America. Deadly in the rush of harvest, deadly in the quiet of fog, deadly in the blur of Saturday nights when the fieldwork is done and the beer drinking becomes a second humiliation. Twenty miles outside Fresno, I cross the Kings, the river that irrigates more farmland than any other river here. The Kings is bone-dry as usual. To find its flow, I’d have to go looking in a thousand irrigation ditches in the fields beyond. There’s a mountain range to my left and a mountain range to my right and in between a plain flatter than Kansas where crop and sky meet. One of the most dramatic alterations of the earth’s surface in human history took place here. The hillocks that existed back in Yokut Indian days were flattened by a hunk of metal called the Fresno Scraper. Every river busting out of the Sierra was bent sideways, if not backward, by a bulwark of ditches, levees, canals, and dams. The farmer corralled the snowmelt and erased the valley, its desert and marsh. He leveled its hog wallows, denuded its salt brush, and killed the last of its mustang, antelope, and tule elk. He emptied the sky of tens of millions of geese and drained the 800 square miles of Tulare Lake dry. He did this first in the name of wheat and then beef, milk, raisins, cotton, and nuts. Once he finished grabbing the flow of the five rivers that ran across the plain, he used his turbine pumps to seize the water beneath the ground. As he bled the aquifer dry, he called on the government to bring him an even mightier river from afar. Down the great aqueduct, by freight of politics and gravity, came the excess waters of the Sacramento River. The farmer moved the rain. The more water he got, the more crops he planted, and the more crops he planted, the more water he needed to plant more crops, and on and on. One million acres of the valley floor, greater than the size of Rhode Island, are now covered in almond trees.

That came from California Sunday Magazine which I'd never heard of; and yet here's how they describe themselves: California Sunday won a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 2021. It was named a finalist for seventeen National Magazine Awards, including for Feature Writing, Reporting, Photography, Design, General Excellence, and Magazine of the Year, and won three. California Sunday was the first title in 25 years to win the National Magazine Award for Photography in consecutive years. Lots of accolades. Why had I never heard of it? All of which brings me to the subject of memoirs (what??).

|

Not all of our memories will be good, but not all will be bad (one hopes). As Pink Floyd sang: All that you do, all that you say, all that you eat, and everyone you meet; All that you slight, and everyone you fight, all that is now, all that is gone. All that's to come. And everything under the sun is in tune...but the sun is eclipsed by the moon. Author Rebekah Taussig wrote in her TIME piece: It feels like we might be approaching some kind of turning point in this pandemic. There are signs that cases are on the decline, and it seems like only a matter of time until the vaccine is available for kids under 5. But what are we supposed to do with these flickers of hope? Can we trust them? We’ve been here before and seen how quickly things can take a turn for the worse. Are we supposed to let ourselves anticipate safety? Order? Reliability? And will it be safe for all of us? Or just some of us?

The point of it all --these collections of past articles, these memoirs, these thoughts swirling around-- is that maybe it's time to start writing and putting things down. It doesn't matter if you get published, or reprinted, or paid...or have an audience of just one, yourself (indeed very few of my friends or family ever read this blog). But whether you write or compose a song or paint a picture or just start a conversation, you will be putting something out there before it disappears...before we disappear. A little bit of you will remain, a memory to someone, perhaps to someone not yet born. As Rebekah Taussig, PhD. wrote in introducing her book, Sitting Pretty -- The View From My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body: This is one of the most beautiful parts of being a human -- the drive to connect and understand, heal and blossom. This is the kernel that takes my breath away. The piece I want to hold on to.

There's been a lot written about symmetry recently, from pieces in the New York Times to Smithsonian. There's even been the Enormous Theorem, recently summed up in a short 350 pages by four mathematicians (the original proof on which it's based runs closer to 15,000 pages), a mathematical study of symmetry, something more than 180 years in the making, said Scientific American. But it's a mess. Said the article: That mess is a problem because without every piece of the proof in position, the entirety trembles. For comparison, imagine the two-million stones of the Great Pyramid if Giza sitting haphazardly across the Sahara, with only a few people who know how they fit together. Basically, the theorem ties everything together; it's how we and everything we know, works (the piece was reprinted in one of the Best American books).

Taussig's brother initially asked her, "What is your writing about? What do you hope it will bring to the world?" Does it matter? She wrote her book; she still writes. Unlike the Enormous Theorem, you don't need 180 years, or a vast readership, or an explanation of why you're doing what you're doing. Some years ago I brought up this same point, saying in one of my posts: You may have dozens or hundreds or thousands of stories or paintings or songs or visions in your head...maybe it's time to be getting them out, setting them free. As Tracy Kidder says, albeit in a somewhat mean way, Who cares? Well maybe now is the time to flip that around to the positive...be yourself, as they say, dance as if no one is watching, be free...because really, who cares?

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.