Missing What's Missing

When the last post featured The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy (it had 3 editions), I was tempted to title that book "audacious" or "admirable" or "ostentatious" because its subtitle was "What Every American Needs to Know." Maybe "pompous" would have been a better word. Admittedly, I bought the book when it first hit the shelves way back in 1988 and indeed found it fascinating, a sort of mini-encyclopedia, one which I begin reading from the opening page. But less than a quarter of the way through, I tired of it, for it was indeed an encyclopedia of sorts, or a dictionary, a book not meant to be read page to page but rather one meant to be peeked at when the urge hit (much as I noted when I used its definition of the word "prejudice" in my post). But step back and imagine that you were one of the authors of the book, perhaps meeting for coffee or a chat, and debating whether you should tackle such a large project (a similar tale emerges in The Professor & The Madman, a Mel Gibson/Sean Penn movie about the creation of the first Oxford dictionary). Jump forward to the founders of Google and their own initial discussion about creating a massive database which would answer whatever questions people may ask...converting measurements, the weather in Taipei, the temperature of the sun, 573 x 866, the ages of Bananarama. With such encompassing projects, where does one even begin? And how long would (does) it take (in the cases of the books, the authors were helped with a slew of fact checkers). Just the challenge of finishing would be daunting...or "preposterous" all definitions that the Cultural dictionary left out, and with justification. Said the opening notes: ...we proposed that many things are either above or below the level of cultural literacy. Some information is so specialized that it is known only by experts and is therefore above the level of common knowledge. At the same time, some information, such as the names of colors and animals, is too basic and generally known to be included in this kind of dictionary. By definition, cultural literacy falls between the specialized and generalized. So the authors then asked, where to begin and how to start the book? Alphabetical? Chronological? Arranged by subjects? They decided to began with The Bible (and followed it with Mythology).

That was another massive undertaking, The Bible, a tome which took nearly 1500 years to complete, said Christianity. As to mythology, the diversifying beliefs occurred even earlier as folk tales began to appear in ancient cultures from Japan to Egypt, and from the Norse to the Etruscan, although one often tends to fall back on the classic Roman and Greek gods and goddesses (indeed, the word "mythology" comes from the Greek definition). Much of this led Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung to shift away from Sigmund Freud, writing: The psyche, as a reflection of the world and man, is a thing of such infinite complexity that it can be observed and studied from a great many sides. It faces us with the same problem that the world does: because a systematic study of the world is beyond our powers, we have to content ourselves with mere rules of thumb and with aspects that particularly interest us. Everyone makes for himself his own segment of world and constructs his own private system, often with air-tight compartments, so that after a time it seems to him that he has grasped the meaning and structure of the whole. But the finite will never be able to grasp the infinite.

Okay, phew...let's back up for a bit. The primary undertaking here is questioning what we do learn and perhaps more importantly, what is it we choose to teach? A study reported in Scientific American pointed out that the wording in textbooks which appear in schools --from K-8 and onward to high school-- depends on the area of the country you live in. The two main purchasers of text books for schools are Texas and California and their "requirements" of what should appear in those books are as divided as our country, especially when it comes to climate change (itself a wording conservatives and some scientists are credited with successfully changing,* mostly eliminating the term "global warming" from current media references). Said part of the article: In 2020 two major education advocacy groups—the National Center for Science Education and the Texas Freedom Network—hired experts to grade the science standards of all 50 states and Washington, D.C., based on how they covered the climate crisis. Thirty states and D.C. made As or Bs. Texas was one of six states that made an F. But because Texas is one of the largest textbook purchasers in the nation—and because its elected 15-member State Board of Education has a history of applying a conservative political lens to those textbooks—publishers pay close attention to Texas standards as they create materials they then sell to schools across America...Most Americans favor teaching kids about the climate crisis. A 2019 nationwide poll by NPR/Ipsos found that nearly four in five respondents—including two of three Republicans—thought schoolchildren should be taught about climate change.

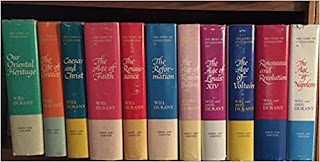

|

| Photo: Society for US Intellectual History |

Think back to the movies you've seen or the books you've read. The basics may be there but the details, well, they're likely to be as jumbled as anything. That was a great show or a great book, you say; but what of it do you really remember? Step back a year or two and those details blur a bit more; step back a few decades and much of it may be gone entirely. Unlike a field where changes may be continual -say a doctor, or pilot, or teacher-- schooling for many of us has both faded and devolved as quickly as a dream, so discovered when I peeked at a biology book and couldn't remember ever seeing such a slew of math equations (the book was a high school text book, for heaven's sake). Most of us had added those school years to the pile of what we learned as a child, what our parents and friends and society taught us. Which begs the question, what's really important to "learn"...to be able to iron a shirt or cook a meal, to have manners and to behave "properly," to change people's opinions or to teach a belief; to simply be kind to all creatures great and small? I ask the latter because of watching a film titled Eating Animals which despite its title, showed more a small number of farmers and ranchers working to preserve a more caring form of domestication, one without mass, unemotional factory production. The problem was, as noted in the film by rancher Paul Willis of Niman farms, he only sold 3000 pasture-raised hogs a week and was up against an industry that slaughters nearly 340,000 pigs day. How do you feed the world at that pace, he asked, and how do you effectively change what the world wants to eat?

So jumping back to how the book of "literacy" which began with The Bible (I should note that the Koran and Buddhism each received a mere two sentences, while both The Bible and Mythology received entire chapters); such a starting point perhaps reflected the mood in 1988 (or perhaps even now in the US, although in today's world mythology might not even be considered). Still, if you were undertaking such a venture, where and how would you start? What subject would you feel was most important to "teach" to readers in a book? For me, I think that I would first eliminate the term of "cultural literacy" (what does that even mean?) and jump right to what every American or person "needs" to know. But again, how would you convince people that they really needed to "know" whatever it was you were writing about? Facts, opinions, studies, observations? And more importantly, why were they so important that the average person not only should, but needed, to know them? Teaching the tenets of The Bible or the long path of history might seem important to you and your editors, but how important would it be to others? Teaching science or literature might seem equally important but again, to how many others? A quick glance at any library shelf will reveal entire how-to sections. Books and videos abound on what to do when you're pregnant, or need to insulate your home, or how to recognize the signs of a stroke or heart attack, or how to begin a budget. So picture the librarian pointing at all of those shelves and shelves and now asking you condense all of that into one volume, telling you that every person "needs" to know those things.

Our interests and "needs" vary almost daily. What fascinates us is perhaps shown by the variety of movies and podcasts, TikTok and You Tube videos, not to mention just the old-fashioned information that emerges from ordinary reading and music. Whatever we once deemed important days or years ago may have now drifted off into the ether, some of it with good reason and some of it to our detriment. The Five Wishes of Mr. Murray McBride offered a somewhat novel perspective of what a 100-year old man does when he encounters a 10-year old child with a heart defect and on oxygen, each well aware that tomorrow may never come to their lives. But within a short time each character in the book is able to witness a changing world, the old man seeing manners and politeness being tossed to the wind (much like today's political ads) while the young one is baffled at his changing hormones and all that goes with a child forced to grow up quickly (kiss a girl, hit a baseball...). Here's a quick excerpt when the kid asks the old man about being a superhero: "You don't want to save the world?" "Save the world? Sure, I do. But I'm a realist." "What's that?" I start to tell him, it's the kind of person who sees things as they are, warts and all. Who doesn't buy into all the rainbows and butterflies some people talk about. Someone who sees that the world can be a hard, unforgiving place. But just before I say any of that, something stops me. Maybe it's the way the kid's leaning forward, like what I say will actually matter to him. Maybe it's the spark in his eye that looks like he wants me to believe in these things right along with him. Besides, a guy gets to be my age, he starts thinking about what he's done with his life. What people will say about him when he's gone...Truth is, I think the world's a pretty amazing place. Not sure when my words and tone stopped saying that. Guess it's easy to get frustrated with little things, and a hundred years'll give a fella a lot of things to get bitter about. But this here kid, he's a doozy. Got handed a death sentence and still runs around laughing and joking. Not taking things too seriously, that's what. The kid's got a passion for life. The reflection of parenting and of being parented boiled down not to what books or videos or lectures taught us, but rather to what we felt was important. Kindness, caring, compassion, listening...and if we happen to "know" a small detail such as how to clear the lint from a dryer, then all the better for passing it on.

The other day, a brand new bright red truck stalled in a busy intersection, as in an intersection with three lanes of traffic in all directions. A quick glance as I turned had me seeing an old man trying to push this brand spanking new --and heavy-- truck out of the way. He was overweight and looked old. It could have been me, not so much in appearance but in having that panicky feeling of your stalled car blocking traffic and trying desperately to just get it out of the way. I pulled off to the side and jumped out, dodging the many cars that didn't stop and were weaving their way through in any manner they could. But as I reached the man and his truck, another young man appeared, his starched shirt hinting that he was heading for work. Then four college-aged "kids" began running up. The old man was exhausted, perhaps too exhausted, even to just get back in his vehicle. Cars continued to weave around us, not honking but also not stopping to ask if we needed help or could block additional traffic. Two of the men slowly, very slowly, helped the old man back in his seat (he didn't want us to call an ambulance), then we pushed his truck back (it was easy with so many of us), then forward, then back with wheels turned and got it safely parked. It was gratifying to me to see that of the many things I had learned from my parents, the rush to help someone was automatic, not only for me but for so many others much younger than me. Perhaps empathy and karma still existed, and that each of us realized that the situation could have been easily reversed, and that any of us would want people rushing up to help us in such a situation. I didn't care about the cars that dodged by us and continued on their way for perhaps something more important was happening in their lives...not my call. But at that point, finishing a book on cultural literacy or world history didn't have an iota of importance.

Final thought: Voyager. Again, an interesting piece on these 2 probes making their way not only further than expected but outliving even the most optimistic engineers. The probes were expected to last 4 years; they're passing their 44th and are now so far away that even at the speed of light, a radio signal sent to them takes 22 and 18 hours respectively (the probes were sent in different trajectories). Here's how Scientific American put it: ...the Voyagers, each about the size of an old Volkswagen Beetle, needed some onboard intelligence. So NASA's engineers equipped the vehicles' computers with 69 kilobytes of memory, less than a hundred thousandth the capacity of a typical smartphone. In fact, the smartphone comparison is not quite right. "The Voyager computers have less memory that the key fob that opens you're car door." Spilker (Linda Spilker, a JPL planetary scientist who still works on the mission) says. All the data collected by the spacecraft instruments would be stored on eight-track tape recorders and then sent back to Earth by a 23-watt transmitter -- about the power level of a refrigerator light bulb. The article continued: Some things outlive their purpose—answering machines, VCRs, pennies. Not the Voyagers—they transcended theirs, using 50-year-old technology. “The amount of software on these instruments is slim to none,” Krimigis (another engineer) says. “There are no microprocessors—they didn't exist! On the whole I think the mission lasted so long because almost everything was hardwired. Today's engineers don't know how to do this."

I probably should have known that; but I didn't. I probably should know more about The Bible, or mythology; but I don't. And if I were British I probably should know that for hundreds of years pretty much anyone could buy their way into being buried at Westminster Abbey, which I thought was reserved "only" for royals and the famous (it wasn't, said a piece in LRB). What we --what every American-- "should" know may be little more than the opinions of those more learned or not, or perhaps simply the views of elected politicians who are making the choice for us...we should know reading, math, science, history and all the rest that is taught in school. And we should know that slavery existed. But what if the question was a larger one...what should another, and perhaps more advanced but likely a non-human species, be taught about us? What information would we feel described not only us as humans, but of our planet? And think of how vastly different our views are today as compared to nearly 50 years ago...or would be 50 years from now.

When the Voyager probes were sent up, NASA had to decide those questions and etched their decisions into copper "records," old school discs subsequently sealed in aluminum coverings for protection. On the discs were no images of war or missiles, or emperors or treasures. Said the article: Encoded in the grooves of the Golden Records, as they are called, are images and sounds meant to give some sense of the world the Voyagers came from. There are pictures of children, dolphins, dancers and sunsets; the sounds of crickets, falling rain and a mother kissing her child; and 90 minutes of music, including Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 and Chuck Berry's “Johnny B. Goode.” Also etched into the discs was a message from then-President, Jimmy Carter: We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.

*Said a piece in The Washington Post: In 2002, Republican consultant Frank Luntz wrote a memo arguing that Republicans start using the latter term. " 'Climate change’ is less frightening than ‘global warming,’ ” he wrote. “While global warming has catastrophic connotations attached to it, climate change suggests a more controllable and less emotional challenge.” The article also noted: A 2014 report from the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication found that the American public is still “4 times more likely to say they hear the term global warming in public discourse than climate change.” The report also found global warming is a much more engaging term. However, the report did show a decreasing trend in Google searches for “global warming” relative to “climate change” since 2007, suggesting the preference for “climate change” among scientists, politicians and institutions may be influencing the public.

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.