Oh Brother...Where Art Thou?

|

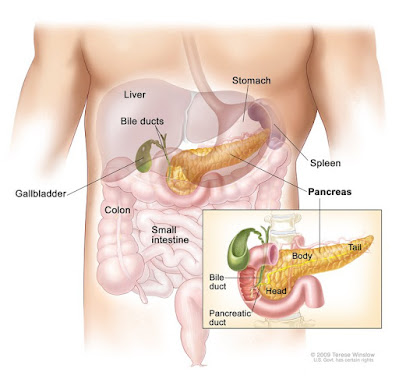

| Graphic of pancreas: National Cancer Institute |

So what the heck does the pancreas actually do? The Cleveland Clinic tried to describe its function in understandable language: Your pancreas releases the pancreatic enzymes into small ducts (tubes) that flow into the main pancreatic duct. Your main pancreatic duct connects with your bile duct. This duct transports bile from your liver to your gallbladder. From the gallbladder, the bile travels to part of your small intestine called the duodenum. Both the bile and the pancreatic enzymes enter your duodenum to break down food. Got that? Me neither. Basically, the pancreas releases enzymes that break down the fats, carbs and proteins in your food, and produces the hormones that control your blood sugar. Yes, understanding the workings of our bodies seems to grow more complicated as we peer inward. It brings to mind that phrase, the more I understand the more I don't understand. Of course, I never would have paid attention to any of this pancreas stuff had this not happened to my brother. Watching how quickly such a condition can take the life of a person, or how difficult such a disease could be to detect early, perked up my antennas. My sister, a retired nurse, told me that we should think of cancerous cells as our body's newest, youngest cells (it's our own cells, after all), healthily gobbling up the nutrients meant to help battle the "sickness," growing larger and stronger and working to overcome the body's other, older cells. It's as if our body is itself trying to figure out, who's the enemy here?

Since the pancreas is so important, or seems to be (it basically breaks down all of the food we eat into something the body can use), then why is it so hard to detect when it starts to get infected? Here's how the American Cancer Society put one area of research about this difficult-to-catch-early disease: Researchers are now looking at how these and other genes may be altered in pancreatic cancers that are not inherited. Pancreatic cancer actually develops over many years in a series of steps known as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia or PanIN. In the early steps, such as PanIN 1, there are changes in a small number of genes, and the duct cells of the pancreas do not look very abnormal. In later steps such as PanIN 2 and PanIN 3, there are changes in several genes and the duct cells look more abnormal. Researchers are using this information to develop tests for detecting acquired (not inherited) gene changes in pancreatic pre-cancerous conditions. One of the most common DNA changes in these conditions affects the KRAS oncogene, which affects regulation of cell growth. New diagnostic tests are often able to recognize this change in samples of pancreatic juice collected during an ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography). And then there's the initial results coming in from yet another vaccine, only this one is meant specifically for those with pancreatic cancer.

Okay, so there's your quick guide to yet another intricate part of your body. And now I find myself sitting here with my sister-in-law, shredding old documents and helping her to transfer titles, making her lists of who to contact and in what order. It's a mess to do for anyone, but something made even more difficult when your mind is just trying to slow down for a second so it can snap out of its numbness. What the heck just happened? At one point, as we notified government and financial institutions of his death, I felt as if I was helping her to terminate my brother's "existence" and I stopped and looked at her. Putting all the papers down I commented, "can you believe that we're doing this?" It was ethereal, hazy, an overload of emotions as if both of us were craving something --sleep, the past, normality, yesterday, his life and years back-- and yet we couldn't understand why all of that was now so evasive. It was the same feelings we had as we walked down that hospital corridor and left his lifeless body alone in the room, watching as the world outside the window continued by as if nothing had happened. People in cars still lined the roads for their morning commute, the rain still pattered on the leaves of the trees and bushes, the birds still continued their wake-up calls. Oh what a beautiful morning it was...except that it wasn't.

Looking back over a few of my notes, I found that I had jotted down this some months ago: The search for something: identity, culture, yourself, your image of yourself...your soul. I saw this come full circle --much like the Native American view of life-- when my brother became a grandparent, his telling me of so many things dropping off: world issues, history's looking back, making sense of mankind. By watching his grandchild grow and learn almost daily, he was seeing a renewal in life and purpose, not only for himself but for his grandchild. The wonder of it all...* I came to realize that for my brother, having spent eleven months in an entirely new phase of his life by being a grandparent was perhaps one of the highlights of his life overall. And I had to admit to myself that I had felt a tinge of jealously when I began to hear less and less from my brother since so much of his time was being spent with the baby: the changes he was seeing, the rapid and perhaps unexpected bonding he was feeling, the witnessing of a fresh laughter that comes only with the innocence at birth. If I were being honest I recognized that I missed the long talks my brother and I shared, talks that I now see were basically fluff when compared to what he was experiencing, that of life blooming in front of him as surely as flowers opening their petals. It was no wonder that he was so entrenched in his new world. It wasn't that I was forgotten, not at all, but there was something renewing life in front of him, something giving him a newly found focus away from things he once thought were important. It reminded me of author Oliver Burkeman who once embraced being productive but now embraced something different, writing: Life is finite and if we want to make time for the things that really matter, we’ll have to learn to let other things go.

To say that I was close to my brother would be an understatement for we not only shared memories of childhood but also those of books and insights, his love for history and his ability to move all those pieces into place often provided me with far more education than what I had retained from my school days. His goodness pervaded his philosophical outlook, and even though he was cursed with an eye that was never better than 20/400, he often read three times as many books than I did, as well as listened to podcasts and audio books and radio interviews. Mention a movie and he would have usually already seen it, but would mention a few additional documentaries or news programs he had also recently watched. Where he found the time, much less the unending interest, just baffled me. He walked for miles each day, often to the library or just to wander about, and rode the bus so much that he gave his son his car. All that and yet he was liked by all, generous of both time and smiles.

Somehow, the image I most remember on that first day of seeing him in the hospital was his look of puzzlement (he was weak but mentally coherent until the last four hours or so); he mentioned to one of the palliative doctors that he was accepting of whatever direction his life took from this point. He had requested that no heroic measures be taken but because of his medical background (he was a physical therapist for nearly 40 years), he was aware of what was or wasn't working in his body as the different meds went in him (the appetite stimulants, the effort to bring down his high albumin levels, the antibiotic drip, the liver scans). The swelling of his extremities increased as the fluids and drugs continued to accumulate and yet not be able to find a way to exit. Potassium and acid levels rose. As we talked so openly, somewhat pretending that a solution was just around the corner and that he would fight off whatever this was, he told me that even at 75 he had "so much more to do" (his words). I was aware that he knew more than most, that medically he could tell that he was rapidly nearing a point where everything inside of him would alter his chemistry and take away whatever control he had left. And still I never saw that he had a fear but rather just his struggling to understand. It was as if he had shifted to a new line of thinking. As Hilary Mantel wrote long ago in a piece in the LRB: When you turn and look back down the years, you glimpse the ghosts of other lives you might have led; all houses are haunted. The wraiths and phantoms creep under your carpets and between the warp and weft of fabric, they lurk in wardrobes and lie flat under drawer-liners. You think of the children you might have had but didn’t. When the midwife says, ‘It’s a boy,’ where does the girl go? When you think you’re pregnant, and you’re not, what happens to the child that has already formed in your mind? You keep it filed in a drawer of your consciousness, like a short story that never worked after the opening lines. The blog piece she wrote was titled: Giving Up the Ghost.

So here I was, shredding away in the small office-like room back at his house, his physical life now gone and me realizing that I was perfectly content to be immersed in a distraction. I could answer texts of condolences with a single and brief sentence; I could snack on foods from my childhood, I could avoid facing the reality that the passing of a sibling in your later years draws you that much closer to the reality of your own end time. I could even avoid writing about the constant influx of emotions bombarding me and instead write about how the pancreas functions, and how quickly it can malfunction. My brother was not an overly religious person; if I had to put any label on his beliefs it would be that of a comfortable Christian. So it seemed fitting that as my sister-in-law handed me yet another pile of papers to shred, out popped a amall slip of paper which he had kept; it was one of those daily quotes from the Bible, Matthew 24:44: Therefore you also must be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an hour you do not expect. But scribbled in pencil underneath that quote my brother had written: If Christ comes today, will you be ready to accept Him?

Peggy Orenstein wrote, in her efforts to learn to knit: ...if I've learned nothing else over the last year it's that "for now" is all we have. Because life, like a sweater, can come together or unravel: slowly, arduously, then oh, so very fast. My brother is physically gone from this world, a world that I realize moves on as if it also knows that there is "so much more to do." So he's gone in that sense, I guess; but in so many ways, he's still here. It would appear that I also still have so much left to do, and that I have so much left to learn, especially that I --just as with the world-- have to continue to move on...

*A few of those thoughts were incorporated in one of my posts, adding this: The focus was now on watching his grandson absorb the world around him, the simple tasks of learning to crawl and watch and smile. My brother now could see that the simple act of providing love to a child was transformative, that (as Gustavo Dudamel said earlier) "they'll create their own future -- their own dimension."

Beautifully written. Your brother would have loves it.

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing this.

ReplyDelete