Biotics -- For and Against

Biotics -- For and Against

Perhaps I should have titled this a different way, say pro and con; but likely you know biotics more in a negative sense...anti-biotics. When I recently had my physical, my doctor had me take some of these, something he knows I'm somewhat adverse to (I'm not a fan of most meds, even taking the occasional multivitamin or ibuprofen just once or twice a year). But in this case, my urine sample showed white blood cells "off the chart," as the lab put it. Did I have any signs of an infection? Yes, I told him, but I had pounded down my own mix of fresh cranberries mixed with oranges, which should have done the trick (in truth, studies of the effectiveness of cranberries on urinary tract infections is mixed, says Web MD, and possibly detrimental). So here's one of the monster antibiotics, Cipro 500 mg...see me in six weeks, he said. The dosage was smack in the middle of most Cipro prescriptions (some are 1000 mg.), one of 20 million Cipro prescriptions written each year (at least as of 2010, says Wikipedia). Also, says the site: As a result of its widespread use to treat minor infections readily treatable with older, narrower spectrum antibiotics, many bacteria have developed resistance to this drug in recent years, leaving it significantly less effective than it would have been otherwise. Resistance to ciprofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones may evolve rapidly, even during a course of treatment. Numerous pathogens, including enterococci, Streptococcus pyogenes and Klebsiella pneumoniae (quinolone-resistant) now exhibit resistance. Widespread veterinary usage of the fluoroquinolones, particularly in Europe, has been implicated. Meanwhile, some Burkholderia cepacia, Clostridium innocuum and Enterococcus faecium strains have developed resistance to ciprofloxacin to varying degrees. And there's the rub, along with all this resistance to the drug by the bad bacteria, Cipro (as with many antibiotics) was fairly indiscriminate, taking out much of the good bacteria as well (new estimates say that it can often take a year or more for the good bacteria in your stomach to return to its normal levels).

Microbiologist Martin Blaser told Wired "that while antibiotics have saved countless lives, they’re an assault on our microbiome." His new book, Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern Plagues, argues that many of the microbes and bacteria we harbor inside of us are necessary and possibly more varied than we think. In an interview with Wired, he said: H. pylori is responsible for 80 percent or more of stomach

cancer cases. But as we were studying it, we kept finding it in healthy

people all over the world. I began to think, “Well, if everybody has it,

maybe it’s not so bad.” Our research shows that people who have H. pylori are less likely to have childhood-onset asthma and hay fever. If one species can have that effect, it’s fascinating

to think about what all the other species we harbor are doing. How many

species are we talking about?

The average person probably has at least several thousand. But we don’t really know...So what do all these bacteria actually do for us? They help us extract energy from food. We’ve outsourced the ability

to make certain vitamins to our microbes. And then there’s defense: The

good guys help us fight off the bad guys. They can also affect the

brain, because a lot of serotonin is made in the gut by neuroendocrine

cells that are in conversation with the microbiota. Where do the antibiotics come in then?

“Why don’t we just give some antibiotics, because it can’t hurt?”

That’s how people think—doctors and patients alike. But our data says it

does hurt...My hypothesis is that every time someone takes antibiotics, a few

species go to extinction in that person. I don’t have proof of this. But

we know that the population sizes of some of the organisms are pretty

small. For 50 or 70 years, everybody thought that if you take an

antibiotic it will have some short-term effects and then everything will

bounce back to normal. But why should they bounce back? If certain less

common organisms disappeared, we might not even know. As Dr. Abigail Zuger reviewed his book in The New York Times, she added: Second, as always, it is the hapless bystanders who have suffered the most — not human beings, mind you, but the gazillions of benevolent, hardworking bacteria

colonizing our skin and the inner linings of our gastrointestinal

tracts. We need these good little creatures to survive, but even a short

course of antibiotics can destroy their universe, with incalculable

casualties and a devastated landscape. Sometimes neither the citizenry

nor the habitat ever recovers.Ahh but no worries since, like me, you probably rarely take antibiotics so you're in the clear, right? Sounds good, anyway. Unfortunately, with up to 80% of antibiotics heading into our cows, pigs and chickens, there may be no getting away from ingesting them. And now we may have reached a tipping point. In a quick summary in The Week, it was speculated about bacteria that "microbiologists warn that it may only be a matter of time before universal drug resistance is widespread and existing antibiotics are obsolete." The Mcr-1 bacteria has now appeared in people in the Netherlands and Britain, France and Denmark; but the bacteria has appeared in China, Africa, and South America as well, from Peru to Cambodia. Says the piece: Mcr-1 is a gene that gives bacteria that carry it resistance to a drug called colistin, the last antibiotic that can cure highly resistant infections. From a human point of view, that's a very bad skill for bacteria to have...But it gets worse: This gene is carried on a plasmid, a mobile piece of DNA that that can be swapped from one bacterium to another within a family like E. coli, but also to other bacterial families as well. This gene can get around. And it clearly has been...After Chinese researchers reported the first discovery of mcr-1 on Nov. 18, researchers with access to databases containing the genetic sequences of E. coli, Salmonella, and other bacteria scrambled to search those collected codes for evidence of mcr-1. The hope, of course, was that this bug was contained to China...Not even close, it turns out. Two weeks later Danish researchers reported finding the gene in samples taken from one hospital patient and five commercial meat products. The earliest evidence of it in Denmark was from 2012. "I had really sincerely hoped not to see it," Frank Aarestrup, head of the genomic epidemiology group at Denmark's National Food Institute, told STAT the day he and his colleagues reported their finding. The poultry meat in Denmark that turned up mcr-1 containing E. coli had been imported from Germany, which adds to the evidence that this gene is hopscotching around the globe.

The suspect is China whose widespread use of the antibiotic (12,000 tons annually) was/is given to pigs destined for human consumption (and export); but the U.S. is mum about its own usage in animals destined for human consumption. As the article continued: These developments come just after Congress upped spending on antibiotic resistance, increasing the pot being shared by a number of federal agencies by $303 million — a 64 percent bump. One might be tempted to see that as a sign that the U.S. government is seized of the threat antibiotic resistance poses to modern medicine. But Price (Lance Price, director of the Antibiotic Resistance Action Center at George Washington University) noted that none of that extra money was allocated to the Department of Agriculture, even though the agricultural sector uses many times more antibiotics than human medicine does.

Still, Nature was a bit more optimistic saying: Although the findings are concerning, they may not be as catastrophic as many media reports have suggested, because colistin is only one of several antibiotics that are rarely used in humans. The discovery “is bad, it isn’t apocalyptic”, says Makoto Jones, an infectious-disease physician at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

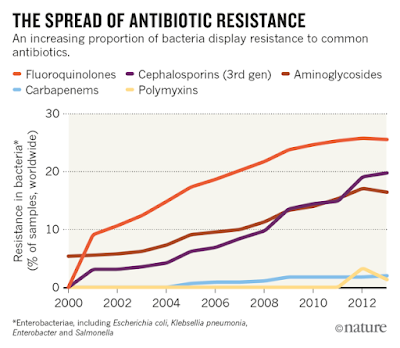

| |

| Source: CDDEP ResistanceMap, based in part on data obtained under license from IMS MIDAS |

As the article further explains: ...the latest findings show that genes conferring resistance to colistin have been identified on loops of DNA called plasmids, which bacteria share readily with one another...Danish researchers have shown that E. coli can transfer its resistance to unrelated bacteria. Colistin is not the only drug that has been called a "last resort" antibiotic. That term is often used to refer to carbapanems, which have mostly been saved to treat only infections caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria. But carbapanem-resistance plasmids have been spreading between bacteria at an alarming rate in recent years...It is only a matter of time, however, before some kinds of infections may not be treatable with any of our current antibiotics. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved about half a dozen new antibiotics in the past two years, and about 30 more are in the pipeline. But most are similar to existing drugs and may not work any better. The most recently discovered class of antibiotics, lipopeptides, was identified in the late 1980s.

There is still hope and one approach is to "squash superbugs." But another is to somewhat declare truce in this war and to recognize that what we're dealing with inside and outside of our bodies might not be all that bad. Researchers on both sides are making slow and steady progress on both fronts. Pro and con, this is once again a complicated subject and once that has implications far beyond our own generation. Part II of this continuing "gut churning" appears in the next post (and again, this is a blog so please do your own investigative research as I only hope to start the discussion going so that you can become aware of a topic and make your own decisions for or against or neutral).

Comments

Post a Comment

What do YOU think? Good, bad or indifferent, this blog is happy to hear your thoughts...criticisms, corrections and suggestions always welcome.